“I’m not a perfectionist,” says the guy who makes niche puzzle games that turn me into a gibbering wreck obsessed with efficiency. And I feel a wave of comical fury. If like me you’ve been whirring and clicking your way through very good engineering puzzle game Kaizen: A Factory Story, you’re probably a fan of previous work from the same developers. The creators of Opus Magnum and Infinifactory may have dissolved their old studio Zachtronics and chemically regenerated as Coincidence Games, but there are still large traces of a Zach present. I caught up with designer Zach Barth to ask about perfectionism, the Factorio-like automation game he gave up on out of boredom, and how the team managed to make a story about factories in 1980s Japan feel human.

Watch on YouTube

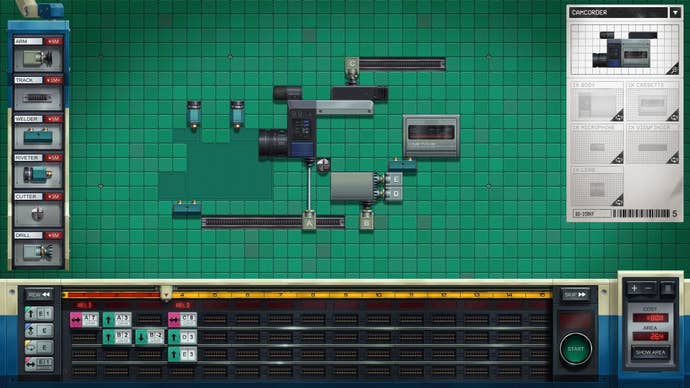

Let’s save the story about the abandoned Factorio-ish game for later. First, a bit of background. Kaizen: A Factory story is a puzzle game that sees you plopping down square-ish pieces of TV sets, toy robots, and gacha-pon machines onto a workspace. Using a whole bunch of arms, drills, welders, blades, riveters, and tracks, you have to create the machinery that will fuse all these pieces together into each product’s final form. As a newcomer to Japan, you are thrust into this world of “lean manufacturing”, where every little step could mean a cheaper, faster, or smaller solution. It sounds like a dry setting, but it’s the perfect place to set an engineering puzzler.

“All of our engineering games have this theme of optimization, right?” says Barth. “You’re continually improving your score and you’re continually getting better at this like a real skill, right? And it seemed to align really well thematically with that vibe.”

While working on the game, Barth bought a book all about the Toyota Production System, a method of factory production that the car company pioneered in the 1980s. The more he read, the more he realised it perfectly suited their games. Even the word Kaizen, he teaches me, refers to the Japanese business practice of “continuously improving” every step in a production line.

“I mean, in tech everybody’s Kaizen-ing all the time nowadays,” says the designer. “It means different things to different people, but one of the things that it does mean is the idea that everybody who’s working on an assembly line is empowered to advocate for quality and efficiency.

“And so you’ll have meetings every day where people are like, ‘Hey, you know, it’s taking me a really long time to do this step. Maybe if we rearrange these things, we can be faster.’ Or… when anybody sees a defective product going down the line, they’re empowered to stop the line because something is wrong further up the line.

“And so it’s this idea that you’re always improving the process because everybody is engaged in the process of making it better. And, yeah, it certainly applies to the stuff we do, but I think that actually it’s kind of the norm now.”

With that constant pushing for efficiency comes a danger, though. The trap of perfectionism has stalled my playthroughs of past games from this crowd, as I search for faster and smarter solutions to early puzzles, instead of carrying on with the next level. It makes me wonder if Barth himself has this problem. If the studio gets as bogged down in the machinery of making a game almost as much as I get bogged down in welding coffee machines together in the most affordable way.

No, as it turns out. Because they can’t afford to waste time sweating every small detail.

“I would say we have our own culture and it’s pretty pragmatic, right? I’m not a perfectionist,” he says, making my nostrils flare. “I don’t know, it varies on a per person basis, I suppose. But we’ve always been in a position where we have to make games quickly because we don’t make enough money off of our games to make it for years and survive off of that.

“Our games are sort of cursed. We have found success, but only if we keep cranking out games really fast. That’s all we’re allowed basically. And so we’ve had to adopt extremely pragmatic approaches with that.”

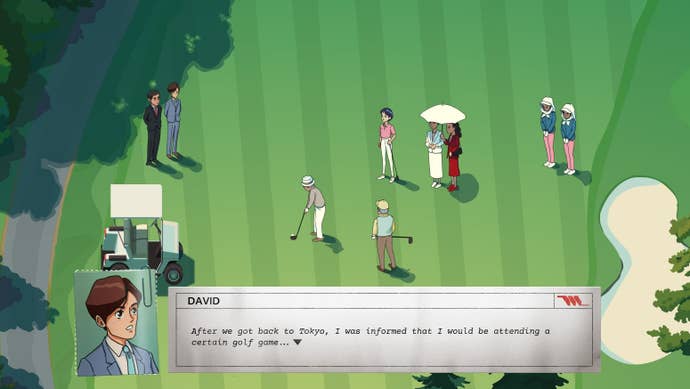

Still, there’s a parallel here, even if it’s not intended. The story in Kaizen follows a bunch of factory workers who are shuffled from place to place by order of higher-ups in a company called Matsuzawa Manufacturing, always getting assigned to new assembly lines. Home appliances. Entertainment machines. Mass-produced clothes. There’s little room for down time. But even applying this to Coincidence Games would be a stretch.

“The story in the game, it’s not really a metaphor for us,” says Barth. “Like, it’s really about trying to situate characters in the time and let them do their thing, right? A lot of our stories are less about a person going on an adventure and more about a bunch of different viewpoints, and then they all interact with each other and you kind of see these like viewpoints play out, and like nobody wins. There’s not a thesis that’s like: ‘this opinion is correct’.”

As a result, it’s a super gentle story, told with the calmness of a slice-of-life documentary. Imagine if somebody took long-running TV documentary How It’s Made, stripped out the terrible music and shot it more like those quiet YouTube videos about how artisans still make certain things the old fashioned way, then passed it all through a visual novel blender.

“It’s a weirdly sober game. It has this kind of non-fiction aspect. And so, you know,

that was a tough task for [writer] Matthew [Seiji Burns] to do. And so, the stuff that we end up with is characters talking about manufacturing. But I like that the characters in the game are really engaged and talking about making things – because the game is about making things! The whole game has this slight educational vibe from being grounded in a time and place in an industry.”

We don’t talk about precisely what’s next for Coincidence (probably another game, duh) but I do ask about one tangentially related trend in PC games – the endless automation game. Your Factorios, your Shapez’, your Satisfactorys. The games Barth designs often end up feeling like a boutique, self-contained antidotes to those grand and endless crafting sims. But the drive for the player is often similar: you want to find the most efficient way to make something. When I probe how he feels about those games, it sounds like he gets asked about them a lot.

“I’ve had meetings and stuff with people who are bigger in the industry and the thing that comes up a lot is: ‘if you could just make a game that was more like Factorio, you’d make a lot of money’.

“And it’s like, if I wanted to make a game like Factorio, it’s not hard to see how to do that, because everybody else is doing that, right? It’s a whole genre now of games that are functionally identical to Factorio. Factorio but 3D. Factorio but abstract. Factorio but… there’s so many.”

But that didn’t stop them from trying at least once.

“Years ago we tried to make a game that was kind of like Factorio,” he tells me. “It was very different. It wasn’t about conveyor belts and all that stuff. You built submarines and kind of explored, and would build factories and stuff. So, it was kind of like a crafting game. But… actually thinking about the amount of work required to put into making it a game, I got really bored really quickly with the idea of the crafting system. Because a crafting system like that is a really obvious puzzle, and it’s just one puzzle.”

“Could I spend a year or two or three making this game that just has a tech tree and that’s the whole meat of the game? I’m admittedly not very good at making all kinds of games, because most of them just seem really boring and you have to spend years working on it, right? Puzzle games are really cool because they’re just filled with concepts, right? And filled with challenges and then you can just isolate and do like a whole bunch of different challenges, because each one is its own puzzle and it’s own little world.”

It’s this devotion to the purity of the puzzle as a form that I think makes games by Coincidence nee Zachtronics stand out. Kaizen: A Factory Story is just more proof, if it were needed, that these niche puzzlers continue to be welded and riveted together in thoughtful ways.