Recently I’ve been spending a lot of time looking down. Not because I’m fascinated by my feet or because there’s dog shit on the street to dodge. There is some, and there was this one time I walked unaware into a fresh pile near here, wearing an open-toed plaster cast, which wasn’t pretty. It went down between my toes, which is, probably, a bad enough experience to change my walking habits, but it’s not the reason I’ve been looking down. I’ve been looking down because I’m reappraising what’s there. I’m looking again at blades of grass to see how tall they actually are; I’m looking again at the skins of fallen berries to judge how strong they’d actually be if woven into armour; and I’m sizing up every insect I see from the imagined perspective of being an inch high. I’m thinking about Grounded.

More specifically, I’m thinking about Grounded 2, but the concept across both games is the same. It’s like the film Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, from 1989, which I realise is a rubbish reference in 2025, but I’ve got an appropriate amount of grey hair to go with it, so you’ll forgive me. The idea of the game, as in the film, is a bunch of teenagers are shrunk down to the size of ants and lost in a back garden, which is now a vast forest to them and filled with dangers they previously – as comparative giants – totally ignored. In order to survive the game, you’ll need to fight insects and harvest their parts for armour and food, a bit like a micro version of Monster Hunter but with base building, which I now realise is a much better reference for 2025.

I’ve been thinking about Grounded 2 because I’ve been reviewing the early access release of the game, and one of the persistent thoughts I had while doing it was, ‘What if Grounded doesn’t work when taken out of the back garden setting?’ Because if you don’t know, Grounded 2 moves from a back garden to a park. A small park – not, like, Hyde Park or Central Park, because that’d be ridiculous. It’d take days to cross spaces that large being so small. So that’s what I’ve been turning over in my head: is this idea forever confined to a back garden? But it just occurred to me how silly I’ve been.

Watch on YouTube

It occurred to me the moment I stepped outside the door and looked down at the ground around me. Imagine Grounded being set here, I thought, in a street in Brighton, with the insects we have, and where a fox might rummage through bins at night, or a flock of seagulls might swoop down to do the same. And where are the worms in Grounded games? We have loads of worms here! And where are the woodlice? Suddenly I was seeing Grounded ideas everywhere.

Then, I spiralled. If Grounded is based in North American gardens and parks, what if you moved it to a considerably different region of the world, such as down in South America, or Europe, or Africa, or Asia, or – oh no – Australasia. Australia’s insects and creatures are frightening enough for full-sized humans, so imagine what they’d be like for inch-high humans. What about frogs and bats and mice and other creatures being in the game? They eat insects. What if they suddenly roared in and upset the ecosystem in the game? The more my mind wandered, the more Grounded possibilities I saw. This concept could work everywhere, and let us re-examine our world from so many different angles.

I was in a harmonious interest loop, in a way, where game reinforced world and world reinforced game. Playing the game made me appreciate my real-world surroundings and my real-world surroundings reinforced my interest in the game. That’s the power a setting like this has. No one needs to sell the allure of riding an ant around a tiny-massive world to me, just like no one needed to sell the allure of Honey, I Shrunk the Kids to seven year-old me back in the 80s. I already understood them because of the real world.

Would the feeling be as strong if you took the survival game guts of Grounded and transplanted them to a nondescript alien planet, where enemies were just as big, and surroundings looked more or less the same, but everything was, well, alien and unknown to you? That would probably never work anyway – the magnetism of the idea comes from the world already being known. But it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot recently, while trying to imagine a world of my own – in this case for a tabletop role-playing game. I’ve got these wild ideas about doughnut-shaped worlds with neverending waterfalls, and planets that procreate – I know, I know – but when it comes to putting this on paper and actually figuring a world out, I stall. Worlds, it turns out – and this might shock you – are bloody massive.

When most people think of making worlds, creatively speaking, they think of small regions to adventure in. They don’t think of actual, global worlds. Let’s test this statement quickly: how many games can you think of that have full, entire worlds to explore? Maybe World of Warcraft or another long-running online game? But even then, they lack the kind of breadth and detail we have in a world such as ours. Even filling one small region with the amount of detail we have in our world is hard, if not borderline impossible. Good luck filling a continent or several continents this way. There’s a reason celebrated fantasy authors like JRR Tolkien and George RR Martin only detail pockets of their worlds and then only roughly sketch the rest, because it would take a life’s work to even scratch the surface of what would be involved. They’d never actually write a story.

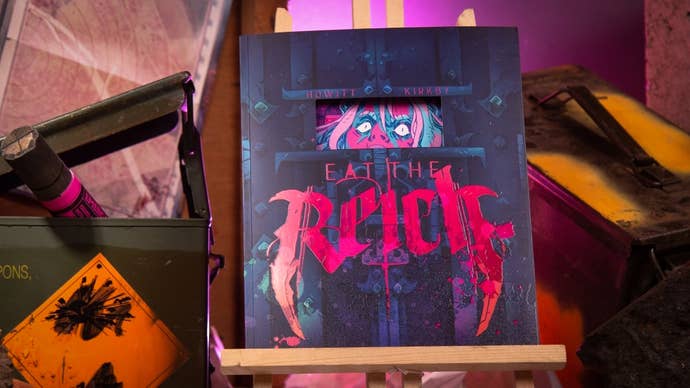

There’s another tabletop RPG I’ve been playing, called Eat the Reich, that does what I’m getting at here well. It takes place in an alternate version of Paris in 1944. You’re a group of vampire commandos coffin-dropped in to kill Nazis and drink Hitler’s blood, which, yes, is an incredible set-up. But it’s made all the more appealing because we know this period of time and know the stakes already (no pun intended). In a sense, the creative hard work of imagining a world is already, organically, done. I’d love it if more games went this way.

Look, I love fantasies and I love fantasy worlds. I’ve consumed a steady diet of them my entire life; and you are what you eat, they say, so I’m happy to tell you I’m fantastical. But while they can be just as luxuriously detailed, and say just as powerful things about our reality through their alternate one, there is just something else, sometimes, to a game set right here. It might seem mundane because we’re in it every day, or like a place we sometimes – perhaps all of the time – want to escape from. But it’s also a place, however mapped and Google Earthed it is, that still holds awe and wonder for us. There’s real beauty in the mundane, when you show it the right way. Grounded and Grounded 2 reminded me of this. There’s magic all around.