“There was a big thing where Sony didn’t like the game when we released it,” Until Dawn creative director Will Byles recalls. “They really hated it in fact, and pulled all the marketing. It was really frustrating.”

It wasn’t the reception Until Dawn studio Supermassive Games was anticipating after spending half a decade developing the now-beloved cinematic horror game, but any concerns Sony might have had were quickly forgotten. When Until Dawn launched in August 2015, it was a critical and commercial hit, scaring up a legion of fans and even winning a BAFTA. Ten years later, Until Dawn is now rightfully considered a modern horror classic, fondly remembered both as a bold experiment in storytelling and a hugely entertaining game in its own right – one that still holds its own today. And with its tenth anniversary now here, we sat down with Byles to discover how it all came to be.

1.

Byles’ career had already been an eventful one by the time he joined Supermassive Games in 2010. He’d started out as an artist before moving into theatre as an actor, director, and prop maker, and it was his skill in model making that eventually took him down a different path toward animation, initially under the guidance of Paddington and Wombles animator Barry Leith, then at famed Wallace and Gromit studio Aardman.

It was a journey that would lead to computer animation and, later, a stint at EA, where Byles – then serving as art director on Battlefield – began dreaming about what else games could be. “I could see a future inside gaming that was more than just hardcore design and much more about the aesthetics, the storytelling, the narrative and beauty of it,” says Byles. And then came developer Quantic Dreams’ Heavy Rain.

“There wasn’t anything really like it out there,” Byles recalls. “Sony, quite bravely I think, went: let’s give that a go, [and] it came out and got a great reception.” It was a success Sony was keen to replicate, and so it approached Supermassive, then a second-party studio, with an idea. “They said to [co-founder Pete Samuels], ‘Can you make a game like this as well?’, and Pete said, ‘Not right now, but I know a man who can.'” And that was where Byles joined the story.

Supermassive’s first attempt at an interactive drama was, by Byles’ own admission, ambitious to the point of unworkable. “It was a non-UI [game] where everything you did was basically a choice all the way through. And it had a sort of adaptive way to deal with stuff; if you wanted to open a door, you could just walk up to it. But [there was] a modifier so if you held the stick forward, you’d basically kick it in… But when we built a prototype, you didn’t know those choices were happening, they just were happening all the time. So that invisibility became its own worst enemy… We pitched to [Sony] which they really liked, but they ultimately said, ‘Listen, it’s a bit too complex.'”

Meanwhile, another project within Sony was struggling to coalesce. “They’d already started making it in Sony’s London Studio and it had problems,” explains Byles. “[So Sony said], ‘Given you’re doing this kind of interactive story stuff, why don’t you have a look at that?'” And that was how Supermassive inherited the game that would eventually become Until Dawn. Known as Beyond, it was a first-person horror title designed for PlayStation 3’s Move motion controller that told the story of a masked killer terrorising a group of teenagers at a snowy ski lodge.

“The way you played it was with a flashlight [mapped to Move],” recalls Byles, “and you had a bunch of QTEs and stuff. There were some great things in it, some quite clever ideas, but it was very literal, and the story was a difficult sell… It was very dark. One of the girls had got pregnant by her boyfriend the year before and had an abortion because she’d spoken with some of her friends. And then this boyfriend had decided to kill everybody who was involved in it. So [Sony] gave us this and said, ‘Listen, please just rewrite this and do something with it because it’s not working [and] we’d really like to push this to another level.’ So I rewrote the whole thing.”

Supermassive’s work on Until Dawn, then still planned for PS3, began in 2011, with Byles drafting a 100-page story treatment charting the game’s journey – minus the branching narrative that would come to define it – from beginning to end. “If that works then that’s a starting point,” he explains. “But if it’s not an engaging story, you start again.” The essence of London Studio’s original idea, though, remained. “It was definitely not [a case of] throwing the baby out with the bath waters,” says Byles. “There were a few names we kept, the balance of eight teenagers, the teen horror… And I personally really like [the mountain] aesthetic. But we really pushed it to a very different level, to a self-aware sort of Scream style… where we started off as one thing, this teen slasher, but switched it around so that’s not the thing at all.”

Byles describes Supermassive’s vision for Until Dawn as a “deliberately pitched” teen horror. “Once it’s up and running,” he elaborates, “it starts to kind of unravel a little bit. A lot of it was designed to really foil your expectations, [so] we intentionally made all the characters very primary coloured to start off with, like a sort of teenager’s facade. [At that stage in life], your biggest worry really is about who you are; we wanted everyone to be at the pinnacle of self-actualisation with all their own little demons and [then, as their survival instincts kick in] start pulling bits away [until they’ve] become a more realistic, genuine person. There was a lot of that, trying to start it off from this position of not ridicule but certainly, ‘We know we’re not a serious horror film-stroke-game.'”

“It’s very difficult working with a publisher on subjective storylines, because everybody above a certain level has got feedback [and] you really do end up in a committee level of story writing where almost nothing from the original has stayed.”

For Byles, though, Until Dawn’s narrative – which gradually swaps classic slasher tropes for more cryptozoological concerns – wasn’t just about subverting audience’s expectations. “I was actually very deliberate in making sure there wasn’t a psycho hitting people,” he says. “A very lazy way of giving jeopardy is putting somebody who’s mentally ill into a position of killing people… I’ve had close relationships with people who’ve struggled with mental illness and I thought, ‘I’m not going to be part of something that’s perpetuating a level of stereotyping.’ [The character of Josh] is suffering badly from the trauma of losing his sisters and is reacting to it in a way that’s maybe not quite proportional, but he certainly isn’t murdering people.”

Another storytelling rule the team adopted came not from movies but rather Byles’ frustration with Heavy Rain. “There’s a bit in the typewriter shop,” he explains, “where you’re playing as the detective and they murder somebody. It happens outside of you knowing it and from then on you don’t know you’re the murderer. And it really annoyed me… that wasn’t just a bit of misdirection, it was an absolute lie. That was being disingenuous. So we had a rule that no player character could know anything of pertinence the player didn’t know.”

With the narrative groundwork laid, Supermassive turned to renowned horror filmmakers Larry Fessenden and Graham Reznick to develop Until Dawn’s initial story outline into a full, and more genre-authentic, script. “It’s very difficult working with a publisher on subjective storylines,” Byles explains, “because everybody above a certain level has got feedback. And that ultimately makes things insanely difficult, even more so when it comes to script and dialogue, because you really do end up in a committee level of story writing where almost nothing from the original has stayed; you’ve ended up with this sanitized, bowdlerised version.”

“So, we made a point of going to find film writers, in a way to try and avoid those conversations over the scripts. We just said, ‘Listen, these people make horror films all the time… whatever they come up with, effectively that’s okayed. No one’s allowed to say it’s not unless it’s broken something, unless it’s breaking the law, or whatever. And then we can have a conversation.'” The hope, ultimately, was that the approach would result in a slightly more sophisticated script than those typically seen in video games at the time.

2.

With Until Dawn’s story pieces in place, Supermassive could start building them out into a game. And while its status as an interactive drama meant player choice was already a given, the team was keen to take things further. “We asked ourselves right at the very beginning really, what’s the important thing in a horror movie? And one of the big things is jeopardy. But in video games, you didn’t really have jeopardy because you could just start from where you left off… So we threw in a rule that everybody can live and everybody can die, [and that] you couldn’t go back… because otherwise death was basically just a failstate rather than a story element. We didn’t want any of that. We wanted [the story] to literally change as you went on.”

As Byles recalls, that immediately made choices more consequential, “because if I die and I’m playing Ashley, and I like Ashley… I’m going to be really, really upset… so that whole thing set up a level of consequence and tension we didn’t have [before].”

But arranging a story around characters who weren’t guaranteed to make it through to the closing credits brought its own complications, which Supermassive approached by developing a narrative structure Byles refers to as the “circles of destiny”. Essentially, this imagines the story as a wheel, with each character’s journey following its own ‘spoke’ from an outer starting place to a converging point in the centre.

“If one of them dies halfway through, the structure is still there,” Byles explains. “All these other spokes are still there. And as long as you meter those out… you can absolutely guarantee you’ll get to the end of the story with at least one or two of those characters just by writing it that way. But that doesn’t mean you haven’t got 50 deaths available up until that point.”

All of which left ample room for different player-driven permutations to Until Dawn’s story, but there were limits. “Ultimately, because you’ve got a finite budget,” says Byles, “the more branching you have, the less you can spend on any one particular branch. So it’s always going to impact the quality and the story. Stories can’t make themselves – they do need to be honed and engineered and worked out – so we had a rule… that if we came up with a really good idea and it was on a branch, the other branch had to be equally as good.”

As it happened, Supermassive’s aborted original attempt at developing an interactive drama for Sony had already taught the team a valuable lesson: that less is more. “We [originally] thought it would be more exciting to have this almost unlimited level of branching, and that’s really not the case,” Byles explains. “People want a really good story that you can control as you go through it… It turns out choices are much more about the appearance of the choice and the feeling you get when you make a choice than the choice itself.”

Byles points to developer Telltale Games’ celebrated The Walking Dead series – and its infamous “X will remember that” prompts – as a great example of this idea in action. “Often they didn’t make any difference,” he says, “but there was the awareness you had as a player like, ‘Shit, that feels like I’ve done something, but I don’t know that I want them to remember that'”. Similarly, Until Dawn’s Butterfly Effect alerts, which would appear in response to certain choices, were designed to imbue player decisions with a sense of weight and tension. “Just going to players, ‘Listen, that’s a thing now’, honestly made such a difference, [creating] that level of expectation and understanding of how consequential things were.”

Not that every choice moment in Until Dawn was equally consequential. “Things happen from all of them,” Byles explains. “It’s just how much happens. I’m loath to say they didn’t [all] matter, but I’m also very aware that [some of them are] cursory. The number of actual Butterfly choices that really made a difference – whether people lived or died because of them – I think was nine in the entire game.”

As the team discovered, though, even choices that appeared minor on paper could weigh heavily on players’ minds. “There’s a funny thing,” says Byles. “As well as the… actual outcome [of a choice], there’s another outcome which we didn’t know about at first but that we now utilise a lot, which is the contextual outcome.”

“If you have a conversation with somebody who has just told you they hate you,” he elaborates, “every part of the conversation that follows is a different conversation regardless. It might be the exact same words and it might be performed in the exact same way, but fundamentally it’s a different conversation because you feel differently about it.”

Among Until Dawn’s myriad choices, there was one branching path the team assumed only a few players would be foolhardy enough to follow – an assumption that proved almost comically wrong once the game hit shelves. In Chapter 9, shortly after learning Wendigos can mimic voices, Ashley hears her missing friend Jessica calling – and players are given the choice to either stick with the group or splinter off to investigate.

“Within a horror context, you stick with the others,” laughs Byles. “Of course that’s what you do. We thought, ‘No one’s going [to investigate]’, but we’ll put it in there anyway.” Supermassive even offered the option to rejoin the group shortly after, assuming players would soon regret their earlier decision. And finally, for those who’d pushed ahead regardless and suddenly found themselves dealing with a violently banging trapdoor, it implemented one last opportunity to turn back and avoid a messy end. “We thought by that stage maybe one out of a thousand would open that trap door,” recollects Byles. “It was 50/50. It was extraordinary!”

3.

While Until Dawn’s choice and consequence system provided a unique way to manipulate tension, its teen slasher trappings meant Byles – a life-long horror fan – and Supermassive could also delve deep into more traditional cinematic scares. “For years I wanted to make the scariest thing there is,” explains Byles, “and I did a lot of research on horror and fear; why some horror films work and some don’t; what goes on physiologically and emotionally. And it’s such an interesting area of creativity because fear is such an atavistic emotion [and] there’s a whole thing about managing that within a narrative.”

Fear can be manipulated through mood, through suggestion, and through other means – but the horror movie staple is, perhaps, the classic jump scare. “It’s really easy to make a loud noise and a big flash of a face, and you literally could scare anyone doing that,” explains Byles. “And Until Dawn has its fair share of jump scares – maybe a little too many for my liking; it’s a [method that’s a] bit cheap and it’s a bit obvious and after a while it becomes quite boring.”

“It’s really easy to make a loud noise and a big flash of a face, and you literally could scare anyone doing that [but it’s a] bit cheap and it’s a bit obvious and after a while it becomes quite boring.”

“There’s a thing about fear… where you can’t be frightened for very long,” he continues. “Eyes dilate and all kinds of things happen to your vascular system, your nervous system. Your breathing changes and you go into a fight-or-flight response state, but that can only last a little while… because your adrenaline starts to drop; your body gets tired and wears itself out… So if you try to keep people frightened for 90 minutes [in a movie] or 10 hours in a game, you’ll fail 100 percent. What absolutely works is if you do that then let it fall away; add in levity, a bit of a love story, it doesn’t really matter as long as it’s not horror or frightening. Manipulating that is good fun to try and do, but I’d have a few arguments about that because ultimately it’s a subjective art form.”

In an effort to ensure its scares were hitting the mark, Supermassive eventually turned to science. “Galvanic Skin Response testing measures the electricity conduction in your skin,” Byles explains, “and the wetter it is the more conductive it is. They put a load of electrodes on your hands, and I think a couple on your head. As you play, an alarm sounds if you go into that arousal state of fear… You can literally watch it in real-time; a player will be walking down a corridor and a noise will happen, then suddenly the little graph peaks. And if you go into a really big scare, it goes off the charts. So it’s a really good way of saying, ‘Okay, it’s not subjective, it’s objectively scary amongst this cross-section of people.'”

As Byles recollects, there was one scare the team was particularly proud of, involving Chris, Ashley, and a locked basement door. “We purposely got it to a stage where it’s very, very tense, and [as Ashley opens the door] we stuck in an over-the-shoulder perspective and put players back in control… Only once they’d started moving forward did the actual ghost come out and scream in their face. It got everybody, but it took ages to design it in a way that made sure that [response] happened each time. It was definitely one of the more technical ones.”

Throw in the occasional splash of gore to complement the tension and scares (“Gross had to be the smallest [part of the mix],” says Byles, “otherwise it starts to become gratuitous and loses strength; it just becomes comedy”), and Until Dawn’s horror language had been defined.

To pull these disparate elements into a cohesive experience, Supermassive homed in on several key mechanics its designers could deploy between cinematic sequences: a choice for players to make, an action scene, or exploration scenes to give the story some breathing room. “It would be, ‘Okay, we’ve got the story, now where should we start putting these things?'”, Byles explains. And over time, the team established a structural rhythm that was intended to keep a balance between its interactive and non-interactive elements, and to ensure players remained engaged. “We tried to keep each [cinematic] sequence less than a minute long,” explains Byles, “less than a page basically, and if you got to two pages, you’d probably pushed it too far.”

As Byles recalls, some of Until Dawn’s more deliberately languid pacing initially proved contentious during development. “There was a lot of resistance to that,” he says, “especially chapter three, when Jessica and Mike are wandering up to the lodge; it takes around 25 minutes and almost bugger-all happens on that entire journey… Ultimately it’s just them having a chat… but we looked at other games like Life is Strange, and whilst it’s not horror, it’s very much about relationships and that’s more powerful than you think. Having access to that within horror became really a big deal. If you don’t care about the people, then you can have as much horror as you like. It doesn’t matter.”

As for that other classic teen slasher staple, sex, Supermassive moved cautiously. “There’s a lot of underlying innuendo [in Until Dawn],” explains Byles, “and there’s obviously the scene where Jessica and Mike can both get down to their underwear… but we were very aware of the level of exploitative sexism that can happen inside these kinds of stories [even though that’s] part of the point of them, certainly back in the 80s. So we didn’t want to be puritanical about it, but we also didn’t want to be gross – it was a fine line.”

4.

Supermassive’s initial PS3 version of Until Dawn featured many core elements carried over from London Studio’s earlier Beyond – the first-person camera, for instance, and a control system built around pointing a Move-powered flashlight. But the release of PlayStation 4 in 2013 gave Sony and Supermassive an opportunity to take Until Dawn’s horror further, and that started with a shift to a third-person camera – something the team had already been tentatively exploring.

“There was a really annoying thing about being in first-person,” Byles recalls. “Having your light source going down the same axis as your viewpoint means you just get flat lighting; you get no side lighting, no rim lighting, no back lighting, and there’s no beauty to it. Every time we went to a cutscene, it was like, ‘My god this looks so much better’. The snow and the woods and the moonlight and the characters, it all looked great. So when Sony said, “Listen, let’s do this for PS4,” we went, “Okay, [but] we need to do it in third-person,” and they said yes.”

“The hard thing was making sure the player wasn’t lost inside that,” explains Byles, “keeping them oriented in the right way… it’s harder than a follow-cam first-person. Way harder. But there’s something potentially very scary about [a cinematic camera]; if I can frame what you can see, I can organise a scare or organise a level of tension just based on that.” Byles points to a carefully framed moment during Until Dawn’s seance scene, one of the few times a genuine ghost appears on-screen. “Beth is just standing in the background and almost no one sees it because we made a point of getting no one to see it.”

The jump to PS4 would also, albeit more indirectly, herald the birth of one of Until Dawn’s most iconic elements: the unsettling psychotherapist Dr. Hill.

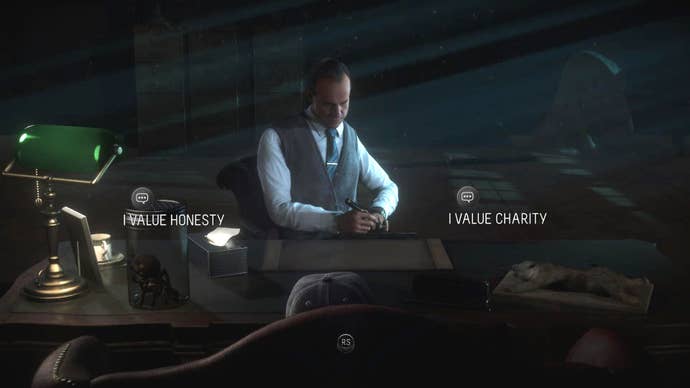

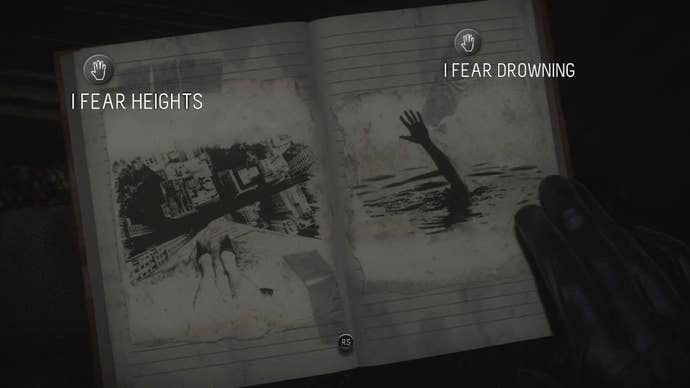

As Byles remembers it, the Hill scenes – where he addresses players directly in first-person, forcing them to make choices relating to their deepest fears – were not in the original PS3 design plan. “We went out to Gamescom in 2014 and we were really aware that the whole choice thing was very divisive,” Byles explains. “People were like, ‘What do you mean by choice? What’s going on with this? You’re not really branching.’ And there was a lot of scepticism around how it would pay off, whether it would make a difference. And the interface, that was a big deal… At the time, as far as I remember, the PS4 still allowed you to use the funny little triangle at the front as a Move controller, so you could make a choice with a joystick or without a joystick.”

With all this in mind, Supermassive built a questionnaire-like level Gamescom attendees would need to complete before delving into Until Dawn’s demo proper. “It was about showing them how to make a choice,” Byles explains, “almost like a tutorial.” And to add a bit of thematic flavour, the team included choices such as whether players were more afraid of spiders or zombies. “[They] made no difference to the game whatsoever,” Byles notes, “but everyone [who tried the demo] thought they did; they thought it was going to slightly adapt their game, to make it more zombie-based if they’d chosen zombies. So, we came home with that feedback and it was like, ‘My god, this is interesting.'”

As it happened, the team had already been contemplating introducing a storytelling element that would enable it to address players directly – specifically to establish the idea that while past events couldn’t be changed in Until Dawn, its choice mechanics made it possible to influence what happens in the future. “And we thought, ‘Okay, this is quite an interesting format; we could tie it into Josh and his mental illness'”, says Byles.

“So it was at that point we decided to kind of fake a first-person perspective where, for a narrative reason, you were talking to a psychiatrist as yourself effectively, and within that you’d be asked a series of questions that would make changes in the game. So you might be attacked with a needle instead of gas if you said you were afraid of needles, or if you say you’re fond of zombies, Dr. Hill literally starts to rot, and he’s almost become a zombie by the end of the game. They were relatively cosmetic, but they were enough.”

The shift to PS4’s more powerful hardware also brought Byles closer to fulfilling another ambition. “I’m probably ultimately a frustrated filmmaker,” he explains. “I wanted to make Until Dawn as close to a film as we could get it.” And PlayStation 4’s increased oomph, in combination with Horizon developer Guerrilla Games’ Decima engine, gave the team at Supermassive the space to pursue a more cinematic ideal. “There was a lot of stuff that we could do that we wouldn’t normally have done before,” says Byles. “So, snow was very good, we got a lot of the new shaders that were suddenly able to be developed.”

“There’s a thing you learn in filmmaking very early on which is that you almost always stick a fog machine into a set before filming anything to give it depth,” he continues. “So, making sure everything in Until Dawn had that on a filmic level – the snow, the amount of dust particles – was huge for believability… and just the way we lit it too; even environments that perhaps aren’t the best looking can look amazing if they’re lit in the right way.” Supermassive even went as far as to give each character their own invisible lighting rig, orientated against the camera norms. This essentially functioned as a portable three-point illumination set-up, helping overcome environmental lighting limitations and enhance Until Dawn’s cinematic feel.

One of Until Dawn’s most ambitious elements, though, was its animation. “I decided I wanted to try and push [things] once we went to PS4,” says Byles. “So we talked to these guys called 3lateral in Serbia who’d been [developing techniques that] meant we could do ridiculously good facial animation for the time. Unbelievable facial animation that was as close to a film as possible… it’s 10 years old [now but] it still knocks the socks off a bunch of stuff today.”

To facilitate that process, Supermassive hired a mostly new cast when Until Dawn moved to PS4, keeping only a handful of actors – including Brett Dalton as Michael and Noah Fleiss as Christopher – from the PS3 version. These were complemented by new additions including Rami Malek as Joshua and Hayden Panettiere as Samantha – who was a well-known face at the time thanks to her role as the cheerleader in hit TV show Heroes. “We pushed for the names,” recalls Bayles, “[Sony] didn’t want names at all… but there was also a budget limit. Peter Stormare [who played Dr. Hill] was really expensive, so we could get him for a day, but we needed some of the people for a lot longer than that.”

“I think as a rule our industry is a little brutal with actors. I think we see them as commodities, and I’ve seen shoots where actors are treated quite perfunctorily.”

Calling on his past experience in theatre, Byles directed Until Dawn’s cast himself. Recording sessions initially took place in LA in 2014, the core group of actors working through 40-50 pages of complex branching script each day. However, practical considerations meant the shoot was limited to capturing facial animation, while body capture happened later in the UK’s Pinewood Studios. These latter sessions utilised different performers, replicating the filmed moves of the original cast. “I now do everything together,” notes Byles, “because it kind of works out better, but in those days it was such a massive ask.”

Byles also believes his experience helped tease out performances that weren’t necessarily typical of games at the time. “Being an actor on stage is really scary,” he explains. “Being an actor in a motion studio is really scary. People don’t get how scary it is… You’re in a white box room studio; you’re in a leotard covered in dots; so unless you’re in good shape, if you’re anything other than buff, they’re not flattering. You’ve got a helmet screwed tightly to your head which can give you a headache and you’ve got to give a performance. It’s a hostile environment… and I think as a rule our industry is a little brutal with actors. I think we see them as commodities, and I’ve seen shoots where actors are treated quite perfunctorily.

“What happens on a game shoot is a bunch of different directors turn up; there’s a performance director, there’s the creative director, there’s the audio director, there’s often the art director, and at the end of every take there’s a discussion and a bunch of feedback given by people who don’t really know how to direct actors. It’s really soul destroying for actors if they’re engaged in the part to be told, ‘Can you do it like this?’ Getting a good performance out of an actor is mostly allowing them to give a good performance as opposed to confining an actor to a very specific set of parameters you’ve decided you want.

“So, for instance, the big performance Rami Malik gave where he’s being dragged to be tied up, which is an extraordinary performance, was me just telling him what was going on beforehand and him just going for it. There are games out there that absolutely do it nicely,” adds Byles, “but the majority don’t… so that had never really been done in that way before and it allowed a subtlety of performance.”

Tying all this together, of course, was sound. To complement audio director Barney Pratt’s work, Supermassive turned to Jason Graves – who was working with Larry Fessenden’s Glass Eye film company at the time – to compose Until Dawn’s score. “He’s a great horror musician,” says Byles, “and if you listen to any of his other work, it’s really evocative. We were very much against going down the big orchestral route because… we’d strayed into mythology – the whole kind of indigenous population level of mythology – so we didn’t feel like we wanted to overly westernise it. We didn’t want to exploit it either. There was a definite conscious decision not to make it [sound] old-school Hollywood and in a way make it more like an indie film.”

5.

Eventually – two studios, two consoles, three versions, and half a decade of development later – Until Dawn was ready for release in 2015. But what should have been a celebratory time for the team at Supermassive was, as Byles recollects, hampered by a last-minute loss of confidence at Sony. “There was a big thing where Sony didn’t like the game when we released it,” he says. “They really hated it in fact, and pulled all the marketing… It was really frustrating.”

Byles blames Sony’s sudden change of heart on a mock review of Until Dawn the company had commissioned about three months before its launch. “The person who did the mock review hated interactive narratives and said, ‘This is a 50 at best’,” explains Byles. “And on the basis of one person’s review, [Sony] just went, ‘Let’s pull the marketing’… I’d written Until Dawn 2. They killed that. It was unbelievable. They thought it was going to go out to die a death.”

“On the basis of one person’s review, [Sony] just went, ‘Let’s pull the marketing’… I’d written Until Dawn 2. They killed that. It was unbelievable. They thought it was going to go out to die a death.”

Sony’s lack of marketing didn’t go unnoticed by the public, either. Speaking to Eurogamer shortly after Until Dawn’s release, Sony Computer Entertainment’s then-president of worldwide studios, Shuhei Yoshida, addressed the situation, claiming the company had decided to focus on “big third-party titles like Destiny” in the run up to Christmas and “didn’t see the need to push Until Dawn that much from the platform marketing standpoint”.

Any fears around Until Dawn’s potential proved unfounded. It launched to a positive critical and commercial reception in August 2015, and would go on to be named Best PlayStation Game of the Year at the Golden Joysticks, even winning a BAFTA for Best Original Property in 2016. “When it did come out and suddenly got a good reaction,” Byles recalls, “lots of people [at Sony] came steaming in saying they deliberately did a stealth launch… It was frustrating.” Even Yoshida later admitted to Eurogamer, “I think everybody was caught by surprise by the positive reaction.”

Until Dawn was enough of a success that Sony later resurrected the series for a PSVR prequel, The Inpatient, as well as a non-canonical PSVR arcade shooter spin-off, Rush of Blood. And while Byles never got to revive his original Until Dawn 2 idea, he teases it was planned to feature the Nixie, a water spirit found in Germanic folklore, as its monster.

As of early 2022, Until Dawn on PS4 had officially surpassed 4m sales, and the public’s ongoing affection for the series has been significant enough to help buoy it toward a revival. Last year saw Until Dawn get the remake treatment on PS5 and PC, courtesy of developer Ballistic Moon, and it received a movie adaptation – one reimagining the game’s core branching story elements as a time loop narrative – earlier this year. There’ve even been persistent rumours, spurred on by the remake’s new endings, that an Until Dawn 2 is in development at Sony’s Firesprite Studio. Supermassive, too, has capitalised on Until Dawn’s success, launching its similarly styled The Dark Pictures Anthology series, and Byles’ own summer camp horror The Quarry.

As to why Until Dawn has endured, Byles – who departed Supermassive in 2022 to found Dial M for Monkey – has a few thoughts. “I look back on it really fondly, and every time I either play it or see it, I’m always amazed at how good it still looks. It’s interesting because I’m working with the literal cutting edge of facial technology at the moment and it’s scary good, but there was a charm to the stuff in Until Dawn that we’re still having a hard time getting.

“I think it was Sony’s most completed game that year, and the number of people who played it not just once but more than once, 10 times, was extraordinary.”

“I think maybe [that’s] partly due to the brewing process. It did take five years to make, even though we made it twice, so there was a degree of maturity in some of the ideas… It was such an effort to make it and such a struggle to put everything new we did in it, and there [were things that] just hadn’t been done before. I think a big part, too, is that it doesn’t take itself seriously… we very purposely went, ‘This is just a bit of fun, come along for the ride’… but done in a really honest way. There’s a kind of truth to it, I think, and we never ever pretended it wasn’t anything but what it was.”

As our conversation comes to a close, Byles shares one last anecdote. “I [went] to do a talk at Middlesbrough University,” he recollects. “I think it was relatively soon after we’d released Until Dawn and I was still very bruised by the negativity that had gone on around it. I went up and there was just love for the game; I was astounded.” And the people that loved Until Dawn seemingly really loved it. “I think it was Sony’s most completed game that year,” he says, “and the number of people who played it not just once but more than once, 10 times, was extraordinary… We started seeing Until Dawn cosplay, tattoos, and I couldn’t believe we’d done something that even on a tiny level had become part of a zeitgeist in a way. And weirdly, as the years go by, it becomes even more so.”