Every October, Microsoft host an Employee Giving campaign for charities chosen by staff, with the company matching any funds they raise. During last October’s Giving month, a group of Microsoft workers organised a vigil for Palestinians killed by the Israeli military during the current invasion of Gaza, stumping up donations for organisations such as the Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund, while paying tribute to fellow tech workers who’ve lost their lives in the war.

“We were honouring the likes of Shaaban Ahmed al-Dalou, who was a computer science student that got martyred in Gaza,” says Abdo Mohamed, one of the organisers and a former Microsoft machine learning engineer. “We were honouring the likes of Aisha Noor Ize-Iji, who was a Washington state resident who had been killed in the West Bank. We were honouring Mai Ubeid, another Palestinian martyr who was a tech worker, and someone who worked with [Google-funded programming bootcamp] Gaza Sky Geeks. People deserved to hear their stories – the Palestinians who had been victims of the genocide deserved a space to be honoured, not to be reduced to numbers.” If you’re a white secular westerner like me, you may recoil instinctively from the religiously loaded word “martyr” here – Bassem Saad has written at length about the history of the term as Palestinians use it to describe those killed by Israeli forces.

The vigil was small – “around 50 people, sitting in chairs side by side, in an open space during lunch hour” – and in line with company guidance for such events, Mohamed claims. But at around 9pm that evening he and another organiser, Hossam Nasr, received an email telling them that they had been fired, with Microsoft later claiming that the event “disrupted” work, and should have taken place outside the campus. For Mohamed, the firing reflects Microsoft’s general disinclination to give employees a “safe space” in which to air their grievances about both Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, and Microsoft’s alleged complicity in supplying technology to the Israel Defense Forces. Rather, Mohamed says, “Microsoft had built this culture of intimidation, retaliation and oppression for anyone who felt the need to speak about what’s happening in Gaza”.

If Microsoft hoped to quell such discussion or at least, drive the issue off-campus, their clampdown on criticism backfired. Earlier this month, current and former Microsoft workers with the No Azure For Apartheid movement occupied part of the company’s Redmond, Washington campus with tents and signs, demanding that their employers cease doing business with Israel’s military. Just this week, protestors held another sit-in at the company president’s office. NAFA members have even pitched up outside Satya Nadella’s lakefront house in canoes. And now, the backlash threatens to engulf Microsoft’s entertainment business.

In May this year, the Boycott, Divest, Sanctions organisation announced a new campaign against Microsoft’s gaming division, calling on people to cancel their Game Pass subscriptions, shun major videogame brands such as Minecraft or Call of Duty, and avoid purchasing Microsoft goods and services. A NAFA petition for Microsoft to divest from Israel has been signed by game developers at prominent subsidiary companies such as Bethesda, Activision-Blizzard, and Mojang. The pressure from within reached a height shortly before Gamescom 2025, with unionised staff at Dishonored studio Arkane publicly endorsing the BDS campaign, and accusing their employers of being an “accomplice to genocide.”

Israel’s ongoing invasion of Gaza is both a response to a massacre carried out by Palestinian militants led by Hamas on October 7th 2023, and a continuation of decades of violent oppression and dehumanisation of Palestinians in Gaza and the occupied West Bank. As of this article’s publication, the number of Gazans killed by Israel’s forces during the invasion stands at around 62,000 people, including over 18,000 children, compared to around 1,800 reported Israeli fatalities, including the casualties from the October 2023 attacks. The majority of the dead are non-combatants: The Guardian recently published alleged Israeli intelligence files revealing that 83% of the Palestinians reported killed in the war’s first 19 months were civilians. Hundreds of thousands more Gazans have been injured and displaced, their homes obliterated by airstrikes. The refugees now face what the UN has called an “entirely man-made” famine brought on by Israel’s refusal to allow sufficient aid into Gaza.

As Israel’s assault has continued, the UN Human Rights Council and Israeli civil rights groups have accused Israel’s government of carrying out a genocide – the most extreme manifestation of an ethnonationalist “Zionist” policy that aims to remove Palestinians from the region of historic Palestine entirely. In November 2024, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and defence minister Yoav Gallant, charging them with “crimes against humanity.” Corporations with Israeli ties have come under scrutiny as potential enablers. In a publication from July, UN special rapporteur Francesca Albanese lambasted the international tech sector for participating in Israel’s “economy of genocide”, noting that “repression of Palestinians has become progressively automated, with tech companies providing dual-use infrastructure to integrate mass data collection and surveillance, while profiting from the unique testing ground for military technology offered by the occupied Palestinian territory.”

Among the companies Albanese spotlights in her report is Microsoft, whose “technologies are embedded in [Israel’s] prison service, police, universities and schools – including in colonies.” Albanese’s account of Microsoft’s role has been corroborated by investigations from the Guardian, +972 Magazine and Local Call, who allege that, following October 2023, Microsoft’s dealings with the Israeli military increased dramatically. Earlier this August, the publications claimed that Microsoft collaborated with Israeli intelligence org Unit 8200 to store and process surveillance data from Palestinian phones using generative AI technology. According to the investigation, this data has helped facilitate airstrikes in Gaza.

Microsoft have pushed back against some of these claims, commenting in May this year that while they have supplied technology to the Israeli military since October 2023, they have seen “no evidence to date that Microsoft’s Azure and AI technologies have been used to target or harm people in the conflict in Gaza.” They have recently announced another “external” review of their business relationship with Israel. But they have otherwise been keeping silent on the subject. At Gamescom this year, Xbox PRs prevented game developers from answering questions about Israeli ties and mass layoffs. Microsoft declined to answer our own request for comment on the recent reporting about Unit 8200.

Microsoft take pride in their humanitarian and philanthropic campaigns, but Abdo Mohamed says that they have long operated a “double standard” when it comes to Palestine, with human resources deployed to intercept and stifle the concerns of workers. Following the atrocities of October 2023, Microsoft sent out a company-wide email expressing support for Israel. As the subsequent invasion of Gaza went on, some Microsoft workers pushed for the company to make another statement, calling on the Israeli military to end the bloodshed.

“There was a petition that was internally circulated for Microsoft to endorse a ceasefire, call out for a ceasefire,” Mohamed says. “And I think at the time a lot of people were starting to speak up internally, using the so-called appropriate channels, which means you ask your executive head of the group, or you ask in this internal forum called ‘senior leadership connection’.”

According to Mohamed, Microsoft management were not receptive to these approaches, even via approved channels. “[We would tell them] Palestinians deserve their dignity, Palestinians deserve the right to food, water, shelter, and so on and so forth. And these questions would get shut down, get dismissed.” Mohamed and his colleagues also tried to organise internal events in which Palestinians would discuss their family histories in the context of the Nakba – the expulsion of around three quarters of a million Palestinian civilians during the Arab-Israeli wars of 1948. “And that event would be shut down, because it was deemed ‘too educational.'”

Mohamed says that other workers were “investigated using weaponised HR policies”, involving “months worth of interviews and intimidation, just for saying something like ‘Palestinians will receive their dignity from the Jordanian sea to the Jordanian river’, or something along those lines.” (For context, the phrase about Palestinian freedom “from the river to the sea” has been interpreted as hate speech by commentators who argue that it implies the destruction of Israel.) Other Microsoft workers “who had been spewing anti-Arab, anti-Palestinian hate rhetoric against those who speak up, had been able to do that with impunity, and without seeing any repercussions,” Mohamed continues. Microsoft declined to comment on either these claims of an HR “double standard” or the circumstances of Mohamed and Hossam Nasr’s firing when approached by RPS.

Mohamed contrasts the corporation’s continued Israeli ties with Microsoft’s suspension of sales in Russia following the latter’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and divesting from apartheid South Africa in 1986. As a former Microsoft machine learning engineer whose projects include Xbox recommendation algorithms and the ROG Xbox Ally, he is especially aggrieved by what he feels is Microsoft’s outright hypocrisy about generative AI.

“Microsoft holds a lot of summits in responsible AI, Microsoft is a guest speaker at the United Nations ‘AI for Good’ summit,” Mohamed goes on. “How can a company, that have been for so long trying to paint this facade, showing how responsible they are around technology and how it gets used – how is a company like that taking this position where they are admitting to working for a military that is on trial for plausible genocide, the generals of that military have arrest warrants taken against them in the ICC, and Microsoft have not taken a real step in cutting these cloud and AI contracts?”

As regards his firing, Mohamed thinks that Microsoft were fundamentally “scared” of the growing criticism of their policy toward Israel, and keen to head off any further employee action. “They wanted to set the precedent that if you speak up, there’s going to be a cost, and that cost could be firing.” He feels that this has proven “a complete miscalculation”, fuelling the outcry over Microsoft’s reported partnerships with Israel – an outcry that has now spilled over into Microsoft’s videogame business.

If there has yet to be a tidal wave of game developers publicly joining the BDS campaign, this is partly because divesting from Microsoft is no mean feat. The corporation’s technologies pervade our culture: 71% of desktop PCs run Windows, and Xbox hardware together with the Game Pass subscription service represents access to tens of millions of players. The BDS campaign reflects the complexity of disengaging by suggesting tiers of protest action: rather than converting wholesale to Linux overnight, it encourages people to minimise or phase out their exposure. Nevertheless, some boycott participants have gone cold turkey.

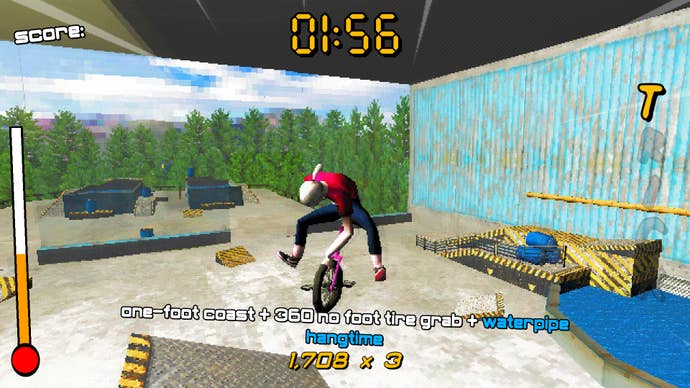

Among the developers who have openly joined the boycott is daffodil, primary developer of stylish sports sim STREET UNi X – a PS1 Tony Hawk game from a timeline in which Tony Hawk traded his skateboard for a unicycle. STREET UNi X has been well-received on Steam, and daffodil had intended to port the game to console via the ID@Xbox programme, but they have now cancelled the porting project to support the BDS campaign.

Watch on YouTube

daffodil sees solidarity with Palestine as part of a wider, holistic struggle that also includes activism against climate change, support for indigenous movements in the colonial territories of Canada, and support for exploited non-human animals. Their joined-up political engagement partly reflects personal, day-to-day experience of transphobia and exorsexism: the developer has recently had to deal with bigoted reactions to their own unicycle performance in the live action segments of the game’s trailer.

“I think my first exposure to the conversation of Israel’s occupation of Palestine may have been through jokes and memes online over 20 years ago,” daffodil tells RPS over email. “I have had an awareness that there was some kind of ‘conflict’ as people called it for most of my life. It wasn’t until around 2021 that I came across Abby Martin and the Empire Files’ reporting on the Zionist occupation of Palestine, and the apartheid state of Israel that I came to really comprehend what was going on there. At that time Israel was actively breaking what was supposed to be a ceasefire, and they were bombing Palestinian neighbourhoods and killing hundreds of people.”

Another developer who has joined the picket is Badru of Ice Water Games, who announced in May that they would pull their weird, brilliant goblin RPG Tenderfoot Tactics from Xbox. Badru is a member of the Palestine Solidarity and Internationalism Working Group via the Seattle chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. “One of my best friends growing up was Palestinian, so I’ve always had some baseline knowledge,” Badru tells us over email. “Still, I don’t think I really understood what was happening in Palestine until some time in the last five or 10 years. Being able to see it so directly on social media has helped. I’ve also been doing a lot of self-education over this period, specifically seeking out socialist history and theory and attempting to understand why the world is the way it is.”

Watch on YouTube

Ice Water Games created Tenderfoot Tactics in their own time and with no investors, splitting the revenue based on the hours of work contributed. The developers “own the IP collectively and democratically decide what to do with it, including the decision to remove it from Xbox”, Badru says. The game hasn’t made “a ton of money”, and the devs have definitely taken a hit by joining the boycott – “a couple hundred bucks a month, maybe”, Badru estimates. He adds that “it’s frustrating having put the work into porting it to the platform”, but that “we did end up getting a lot of visibility and support after our announcement, and saw a brief but very significant sales boost on Steam which probably will more than make up for the lost income from Xbox.”

Divesting from Xbox is a bigger deal for daffodil. They created STREET UNi X in their off-hours while working cash jobs over the first four years of development. It wasn’t till they teamed up with worker cooperative Gamma Space and Weird Ghosts, an impact fund for underrepresented developers, that they were able to focus on the project full time.

“STREET UNi X is what I consider to be my first polished commercial video game, my first game released on Steam, and a project that I spent over six years working on,” they say. “I have been struggling to make headway releasing the game on consoles. I initially sought to release it on Nintendo Switch, and have applied to be a Switch developer repeatedly since at least a year before the game released. I have been denied Nintendo Switch developer access eight times now with no word as to why I am being denied.” (At the time of our conversation, daffodil had just received another rejection email from Nintendo.)

A console release could make a “huge impact” on daffodil’s fortunes, given the game’s positive Steam reception. “As much as I would like to be, I am not able to rely on my games right now to cover my living expenses,” daffodil says. “I am currently doing contracted level design work to pay my bills.” daffodil has also sought to release the game for PlayStation, but found this impractical due to the expectation of a static internet protocol and office email address. Microsoft’s comparatively accessible ID@Xbox programme was their best opportunity to get “a foot in the door.”

Microsoft did not respond to the substance of daffodil’s objections regarding Israel and Palestine when they announced that they would pull the port, merely sending instructions for the deactivation of their accounts and the return of development hardware. “I find myself combating a deep sense of let down,” daffodil tells us, “knowing I either do not have access to this opportunity in the case of Nintendo and Sony’s consoles [or] have had to contend with the fact that working with Microsoft means they will profit from my labour, and use that profit towards the ends of perpetuating injustice the world over, and in the Zionist occupation’s case, provide Azure and AI tools to Israel’s occupational forces to actively slaughter, starve, torture and otherwise dehumanize the people of Palestine.”

It’s easy to be cynical about the potency of consumer boycotts, and it’s true that few boycotts force an immediate and miraculous change of direction; when they do, there are often wider, linked considerations, such as anxiety about lawsuits. It’s even possible for a boycott to rebound in the targeted company’s favour, as when Nike made a $6 billion revenue gain helped along by consumer reaction against protest over adverts featuring Colin Kaepernick. But there is a substantial history of boycotts helping to bring about meaningful change, including a number of successful pro-Palestinian actions against companies and institutions like Puma, Barclays, and Pret over the past two years.

In 2020, Microsoft themselves announced they would divest from an Israeli developer of facial recognition technology used at checkpoints in the West Bank, following an outcry from civil liberties groups. As with the 35-year-long boycott of South Africa, boycott organisers need to think long-term, which is why BDS aren’t insisting that people dispense with Microsoft’s services entirely to qualify as participants.

daffodil attributes some of the wider developer and player reluctance to join the boycott to cultural privilege – “when we can’t see the problems in front of us we get to relax.” But they also argue that it reflects an atmosphere of “generalized nihilism” in the face of disaster. “We are convinced that caring too much is cringe,” they say. “We are constantly shown that if you care too loudly you will lose your job, or your family, your community, and that you must fall in line or else. I’ve lived through so many such shutting outs. I’ve lost friends, I don’t speak to my family much at all anymore, I’ve been fired from jobs for trying to organize the workers.”

It is, they note, especially hard for developers to speak out during a time of mass layoffs: “The world has been built up in such a way that we are made to be afraid to rock the boat too hard, lest we become the target.” As such, part of the reason daffodil joined the boycott was simply to remind other workers of their own power to bring about change. “I am trying my best to encourage others to take a stand themselves,” they tell us, “but I worry that I don’t have the levels of clout or power in the video game world that some seem to hold as a prerequisite to take seriously such calls for total liberation the world over.”

Badru argues there is a lot more support for Palestinians than you might guess from the shortage of official BDS endorsements. There are various more immediate practical challenges, he notes. “Some [developers] are unable because they don’t have control over their relationship to storefronts, and/or they don’t have full control over messaging around their game,” says Badru. “Because of the controlling nature of publishers, or because of deals they’ve signed with Xbox.”

“Unlike us, many do significantly depend for their livelihood on income from Xbox sales,” he continues. “And so making this decision is much more difficult for those teams, and would potentially result in closing down their companies or laying off some employees. Most game companies are run undemocratically by their owners, like nearly all companies. The owning class is significantly more likely to prioritize profit over people, and also to be in favor of the genocide, or at least ambivalent about it.” He also points out that some videogame and software companies are disinclined to criticise Microsoft because they also work with military organisations – Microsoft’s own defence industry contracts extend far beyond Israel.

Badru expects the number of endorsements to grow, once some of the above practical difficulties are resolved. “For teams that would like to support Palestine, it is still complicated and difficult to make this kind of action very quickly,” he says. “Game development business plans are laid years in advance and generally include target platforms. Often, funding for a game is related to release on a storefront. Say a company is part way into development on an Xbox game, and is unwilling to dissolve or significantly restructure their team in order to cut Xbox out. They’ll need to finish the current game, release it on Xbox, and then as part of their next game’s development plan, choose to target other platforms. This is the kind of boycotting that I expect will be more practical and widespread, because it causes less chaos within companies.”

The other pressure here is, of course, the audience. There continues to be a vocal group of reactionary players who regard games as a refuge from political engagement, even if they have no specific stance on Israel and Palestine. To join the picket is to brook their ire.

Badru baldly observes that “a lot of our audience are children, or wish they still were” and that games in general “are less accessible to poorer people, or people outside of the imperial core” who are necessarily more politically aware and engaged. “That said, our experience [during the boycott] has been one of overwhelming support,” he goes on. “Like you say, maybe it’s due to our place in the independent sphere. Maybe it’s because we’ve always been political and so have cultivated this audience.” In his wider work, Badru has found that “the public is actually very pro-Palestine and happy to talk about it”, more than one might expect from heated conversations online. “I believe this is true of the games audience as well.”

During our interview, Abdo Mohamed doesn’t speak at great length about how being fired by Microsoft has affected his own livelihood and career as a technology worker. But he does comment that leaving the company has given him moral clarity. “Seeing the role of the company in Israel’s apartheid and genocide, and not being able to speak up for my principles, and not being able to speak up for my morals, and not being able to put people over profits, had always been a challenge,” he says. “Every time I censored myself during my time at Microsoft it made me question if I really stood for those principles.”

Mohamed never contributed to any of the services that are reportedly in use by Israel’s intelligence divisions – or at least, not directly. “My background is in machine learning and AI, but I was lucky to be not working on this technology that has been weaponised,” he says. Given that generative AI software relies on access to data to “train” the models and improve their responses, it’s hard not to wonder whether anything from the reported Israeli surveillance collaboration has made its way back into Microsoft’s consumer-facing cloud and AI services.

Mohamed suggests there may be a firm distinction. “It’s really unclear to us how the surveillance data is fed back to Microsoft, because it seems from the framing that this is top-sensitive data, so it doesn’t get used for the training of the models.” He argues, in any case, that whether Microsoft have made wider use of any of data gathered in the course of partnerships with the Israeli military is not important here.

“There were people who were directly working on that technology, in our worker base. But it didn’t matter what technology you were working on,” he says. “You were a worker for Microsoft, your labour, whether you agreed to it or not, was being used. If I had worked on an Xbox project, and that Xbox project had launched a successful feature, and that successful feature ended up generating revenue for the company, that revenue is eventually being redirected to build the data centres, it’s being redirected to fund the research projects, it’s being redirected to enable the resources that eventually get used to provide something like the Unit 8200 mass surveillance weapon.”