Sucker Punch’s sequel offers more great swordplay and heartfelt storytelling, but would be better served as a linear action game, freed of its poor sidequests and dated open world.

I still can’t figure out how to think about Ghost of Yōtei. And, honestly, its predecessor, Ghost of Tsushima, even four years on. I enjoy these games – I enjoy these kinds of games, even. I’m a sucker, if you’ll forgive the pun, for the Sucker Punch style of open world. A kind of Diet Assassin’s Creed: even lighter; even shallower; even simpler to grasp and follow around, sword in hand, air in head. Sometimes with video games and their often unfathomable complexity and depth, these games feel like just about all I can handle. Sometimes you just need Love Island, Emily in Paris, an infinite, blue-lit bedtime scroll. And sometimes you snap out of it.

The thing that keeps me in the camp of the first option here, the camp of willing lobotomisation, is a desire to try and meet this game on its own terms. Forget what Ghost of Yōtei is for a second – and especially forget what it’s saying it is – and instead just focus on what it’s actually trying to be. In this sense Ghost of Yōtei is more like a success. It’s trying to be a breezy hell-yeah action game, wrapped in the aesthetics of hell-yeah samurai movies – less Kurosawa, more 13 Assassins, more “mud and blood”, more explicitly Western-style samurai movie. It’s also not trying to be clever about this, or at least I really hope not. Western movies are in the most reductive way about lone wolves imparting justice on the land; in Ghost of Yōtei there is a whole mechanical system built around, well, a wolf. Your allies – actually just vendors, let’s be honest – are called your Wolf Pack. We’re not aiming for subtlety here.

The setup this time, as it is with just about every don’t-think-too-hard action flick, let alone triple-A action video game, is a good ol’ tale of revenge. As a child, Atsu’s family was brutally murdered by a group known as the Yōtei Six, led by the villainous Lord Saito. With her mother and father slain before her, and her brother never found again, Atsu was left pinned to a tree by her own father’s sword, that tree subsequently set alight and Atsu left there to die. This, and a fiery, immaculately staged Western scene where, amongst some deft tutorialisation, you ride into a rotten town, flush out some drunks from a building and scythe down the Snake, the first of the Six, make for a cracking opening. Your savagery and blunt refusal to die in this prologue earn you the nickname of Onryo, a vengeful ghost returned from the dead, and quickly that legend overtakes you. First hell yeah: achieved.

Soon enough, we’re back to the ‘Ghost of’ classics: galloping through long grass, following the wind, rolling into minor settlements helping villagers with little favours. The structural tweaks to Ghost of Yōtei are dressed up as significant, but ultimately quite minor. The world, rather than the two halves of Tsushima, is now split into five-ish parts. The first, a kind of double-sized area, is made up of largely grassy, low-hilled wetlands. There are as many side activities here as any of the others – if not more – but the sooner you can break out into one of the other areas – each dedicated to a Yōtei Six boss and their specific brand of territorial cruelty – the better. Yōtei is wetter, bleaker, intentionally greyer than Tsushima. A stormy game, less overt in its big swings at beautiful scenery and more focused on quietness, the way the light passes through trees. (Admittedly, it does still love to kick up lots and lots of brightly-coloured leaves when you walk through them, but whatever. It looks nice!)

As for those proposed changes, a key one is a suggestion that Ghost of Yōtei’s exploration is more ‘clue-based’ and contextual. I can’t say that really stands up. You will primarily be following the wind here again, an aesthetically pleasing but ultimately very simple replacement for the classic waypoint. I mentioned this when talking about Tsushima previously – so many points about that game apply again here – but this is ultimately just the infamous Bioshock Arrow at the top of your screen, a giant hand pinching you by the nose and dragging you to your chosen destination. Likewise, the golden birds return, appearing and guiding you – like the wind-arrow – to a not-so-hidden side activity when one’s nearby. Often quests might give you a bit of detail and an area to search, which is slightly more clue-based in theory: look for the golden mother-daughter tree, for instance. The only issue there is that these tasks aren’t exactly hard; in a forest of snow-covered trees a single, golden yellow one that shines so bright it could be seen from outer space is not the most challenging to track down.

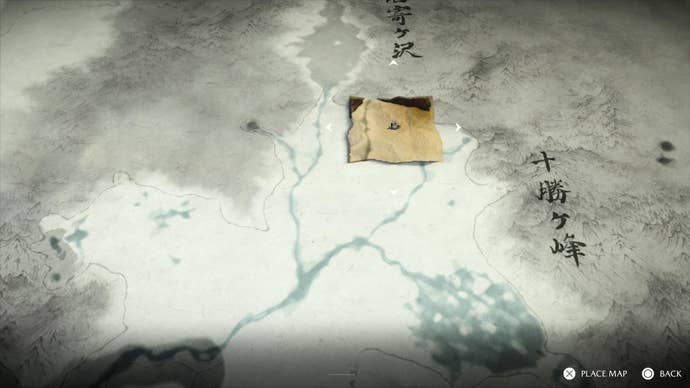

The same goes for the other new system added to exploration, in maps. You’ll get these from picking up occasional scuttlebut from talking to NPCs, or you can buy them from the map merchant, who like all merchants is – don’t think about it too hard – present and available at every single settlement you visit and also frequently turns up whenever you pause to make camp, even if that’s at the top of a mountain or in the middle of a raging warzone. I love the idea of them: little squares of paper with sketches on them outlining a few identifiable parts of the main map, and whatever secret (usually an Altar of Reflection, which you get a skill point for visiting) they’re helping you find. You have to match the sketch to the right location on the main map itself, which is a very neat idea. Unfortunately in practice, like an awful lot of Ghost of Yōtei, it is unbelievably simple. The maps are locked to the relevant region, giving you a pretty small area to search, and will lock into place even when you’re only vaguely in the right spot. Given the size of the regions – not huge – and the numerous identifiable parts of the topography like river bends or shorelines, not one of the dozens of these I uncovered took more than five seconds to correctly place.

That unfortunately speaks to a wider issue with Ghost of Yōtei: quite often this game does treat you like an idiot. This is an issue with triple-A gaming as a whole these days, of course – Yōtei’s far from the only culprit – but it does seem to have a particular knack for it. While it does an excellent job of removing hand-holding UI clutter – often it’s entirely absent, which is a genuine achievement for this type of blockbuster open world and should absolutely be praised as such – it also can’t help but backseat drive at the first fraction of a second pause. Take climbing, for instance: Yōtei’s climbs are entirely restricted to grey ledges – grey a slightly more artful replacement for Tushima’s yellow paint here (though this can sometimes feel like an attempt to defeat the “yellow paint” meme by making the paint a different colour, rather than adding smarter contextual cues or just having the climbing mechanic work differently.) It’s all very familiar: most of the time you climb these narrow pseudo-ladders up the side of cliffs by just pressing the L stick in the direction of the pre-marked path, but occasionally there is a small gap for you to press X to jump. If you so much as dare to press X to try and jump-climb a bit faster, or scale a gap that looked like it needed a jump, or stop to scratch your nose, a big “PRESS L TO CLIMB” descriptor appears. You might find you’ve already gathered that, half-way up a mountain, 20 hours into this game.

Yōtei’s puzzles are similar culprits. This time the verbal hints are less of an issue – it’s no God of War Ragnarok or Horizon Forbidden West in that sense, thankfully – instead it’s just the puzzles themselves, which are simple to the point of parody. Or just to the point of pointlessness. Before you sit three fox statues in different poses. Behind them, another statue of a fox doing one of the poses. Press R2 on the statue that matches it.

It’s easy to wave these things away as nitpicks, or minor inconsequential flaws (the climbing tip is really nothing, but just a perfect illustration of Yōtei’s wider approach) but doing so misses the real point. The result of all this relentless hand-holding is a kind of flattening effect, a deadening of reward. Breaking into the lair of the infamously untraceable Kitsune, or tracking down some mythical suit of armour in a far corner of the map, doesn’t feel like the slightest achievement because it requires nothing of you, beyond crossing your arms over your chest, sitting down, and allowing yourself to be pushed over the top lip of the water slide. The rest of it is all downhill tunnel, closed on all sides, a few gentle up-and-downs without risk or peril. To think too hard about any specific puzzle, challenge, or moment in Ghost of Yōtei would be to try and chew a milkshake. Better to pull your teeth out altogether and save the brain-freeze.

The impression is that Ghost of Yōtei is a game that wants to sand its rough edges down to the point of total sphericality. It wants you to not have to think about it. To not ever be stuck or frustrated, outside of maybe its biggest boss fights (which, even then, rarely offer a challenge and respawn you instantly, often at mid-fight checkpoints, without punishment or judgement). It’s structurally a linear game, in fact: any missions beyond the basic side quests will typically take place in a strictly linear space – a single-route mountain platforming path, a follow-the-NPC stroll, a largely locked-off enemy encampment or castle with one, faux-open way forward.

I’m being a little harsh here – I like milkshakes! And water slides! The point is less that this type of game is an issue – linear can be brilliant, for instance, a perfect vehicle for the kind of melodrama, storytelling and bombast the first ‘Ghost of’ game loved – but that in burdening this type of game within an open world we end up in a kind of rigid in-between. And that Sucker Punch, for whatever reason, has failed to improve on the many issues with the studio’s first attempt.

There are more open world tasks in Ghost of Yōtei, for instance – you can now seek out Wolf dens and follow them on a fun gallop to a nearby wolf-hunting camp to enact some sword justice – but the issue was never the quantity of things to do. It was that each subcategory of thing-to-do was, after a short while, really quite repetitive. Petting a cute fox after it takes me to a little collection of pickable flowers and gives me a charm is lovely. Doing it half a dozen times, heck even doing it three times, gets old fast. Moments that would make for great, one-off sidequests instead become checkbox busy work, means to an end – another minor charm! – as opposed to ends in themselves.

Likewise, those sidequests, the low point of Tsushima, are again the low point of Ghost of Yōtei. Once again, sidequests amount to helping nameless NPCs with comical busywork that inevitably ends in killing six-to-twelve bad guys. One, I thought, was surely setting me up for a fun little subversion of that: a guy asked me to help him with the ‘simple task’ of cutting some bamboo in his garden, which I did. Then six-to-twelve bad guys turned up and I killed them.

More involved sidequests, meanwhile, have if anything got worse. The performances of Tushima’s brief-but-interesting encounters are never matched by the various senseis you encounter here, which all devolve into a very basic series of tasks you’ve already completed elsewhere – clear out this enemy camp, fully upgrade this new weapon’s skill tree, etc. I’m somewhat stunned by the lack of improvement here: such a clear weak spot, for a game with so much potential, and likewise a spot that could also be the game’s greatest strength. So clear is the lack of improvement that I had actually made a note to reference The Witcher 3 in this review, as an exemplary case of not only proper open-world game sidequesting but also a Western, based on a lone ranger riding into town and helping out the little folk. Then I realised I’d already written that in my Ghost of Tsushima review. This was four years ago, when Ghost of Tsushima’s sidequests already felt outdated. Here they’re prehistoric.

Combat, thankfully, at least remains a good time – and is also a case of genuine improvement on the first game. The camera is better positioned, and there’s a lock-on option if you want it, though the improved camera largely solved the issue of getting side-swiped by off-screen enemies for me anyway. There’s also a much better range of enemies to slash away at here, and a better distribution of skills with which to deal with them – no skills or items I could find that made all attack types parriable, for instance. The flipside is that combat can, fairly often, devolve into some slightly rote rock-paper-scissors encounters.

Shield enemies are now best dealt with via the Kusarigama, for instance, a lengthy chain with a shield-smashing ball at one end and body-slashing scythe at the other. Scythe-wielding enemies are best defeated by a spear; spear-holders by duel-wielding katanas; giant enemies with, well, a giant sword. The upside is the novelty and dynamism of switching between weapons rapidly on the fly – and, in particular, the gloriously savage spectacle of eviscerating enemies with two katanas at once. The downside is the relative lack of flexibility: your katana is always at least fine as an option, particularly with a few early special moves unlocked, but all other weapon types are largely ineffective against anything but their designated counter. It’s often a case of starting out by having fun, living your sword-wielding fantasies, dodging and parrying poetically, stoically, resolutely, then a shield guy comes out and you have to do the ball-and-chain thing for a bit before you can go back to the good bit.

What remains, nevertheless, is a really sharp combat system. That old hybrid of Arkham and Sekiro continues, though the trademark flow of parries and counters has become ever more prevalent since Ghost of Tsushima arrived in 2021. Here however it’s still wonderfully honed to the character at hand – a sad and furious Atsu, a wounded animal – who’s animated with glorious brutality and poise. There remains nothing cooler in third-person action games than Atsu, standing head to toe in mud and blood, surrounded by the despatched bodies of dozen arrogant grunts, flicking her sword free of their blood and slowly guiding it back into its sheath.

Likewise, a few new tricks add a bit of variance for when the new weapons get a tad stale. While I never found Yōtei’s ‘builds’ system to be of much use at all, given the relative inflexibility of the systems at hand, I did find one way of indexing a bit more towards a certain tactic. I found some armour and skills that, together, extended my assassination streak and let me lob a kunai or two at the end as well. Coupled with smoke bombs, which let you disappear in a flash, you could go full shinobi here when surrounded: drop a bomb, assassinate three in quick succession, lob a kunai at another, and in a split second you’ve wiped out a whole group – all with, naturally, an abundance of choreographic flair.

As with Ghost of Tsushima again, Yōtei’s performances and facial animation – at least in the flashiest, pre-rendered cutscenes – remain a highlight. Presentation as a whole can be quite a mixed bag: those pre-rendered cutscenes are gorgeous, intricately lit, photographed as an immaculate facsimile of Western style and staples, all letterboxed eyes and doorway silhouettes. The in-engine cutscenes of which there are far more, are a little clunkier, while on-the-ground conversations are, unfortunately, really quite dated again. Expect a lot of very wide, slowly panning shots of two static marionettes wagging chins at one another in an empty field, maybe with a skidding bear in the background. I don’t particularly mind this – video games! It’s what they do – but in a game that makes such noise about its cinematic inspirations, it just doesn’t fly. You can’t invoke the name of Akira Kurosawa, of all directors, even once, and get away with this.

Still, the performances: Erika Ishii gives a pouty, sullen, but sincerely vulnerable and authentic turn as Atsu here. Lord Saito, her arch nemesis, has the perfect gentleness and unnerving warmth to offset here: a cruel villain with a cuddly aura and sad eyes that imply a cycle of harm, as opposed to plain old evil. That, also, is Yōtei’s storytelling strength. Ostensibly this is a revenge story but really it’s a story of trauma and its recurring nature, laden with anguish, genuine pain, angst. Again, subtlety is often left at the door – Yōtei’s biggest moments are repeatedly predictable – but in an action flick that’s fine. Without spoiling anything, the only issue is Atsu’s arc – as with any for a character who begins at peak vengefulness and must go somewhere, in 30-odd hours of narrative time – is hard to reconcile with where the plot needs to go by its conclusion.

As with so much of Ghost of Yōtei though, this all works much better when you just don’t think about it. I don’t mean this, really, as a pejorative. Without the overly po-faced, grandiose vibes of the first game, Ghost of Yōtei has a clearer vision of what it is. There’s less of the clash between modern, populist Hollywood and the classics here, less of a tension between high and low art, entertainment and art, art and not-art, however you choose to define it. This is just straight, well-trodden blockbuster stuff. Sometimes that’s all I’m after. But often it does have its flaws.

A copy of Ghost of Yōtei was provided for this review by Sony.

.png?width=1200&height=630&fit=crop&enable=upscale&auto=webp&w=880&resize=880&ssl=1)

.jpg?width=1200&height=630&fit=crop&enable=upscale&auto=webp&w=360&resize=360,270&ssl=1)