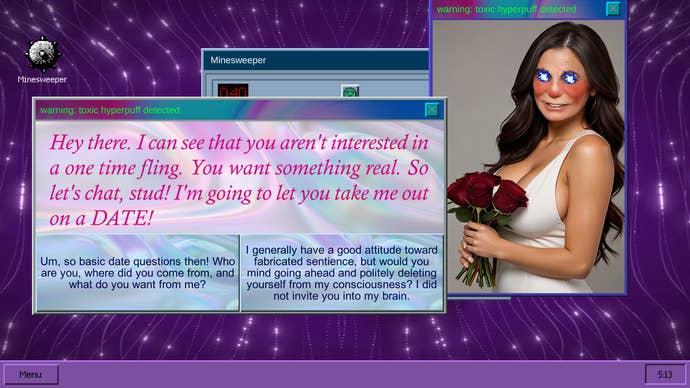

To speedily summarise a lot of very knotty reporting, last month a bunch of credit card companies and payment processors forced Steam and Itch.io to alter their definitions of acceptable sexual material in PC games. Seemingly faced with the prospect of having all transactions blocked, the two storefronts now require developers to comply with the extremely open-ended adult content policies of their financial partners. This has led to a spate of delistings or outright takedowns across Steam and especially Itch, with projects affected ranging from anime stepdaughter fantasies on Steam to bundles of self-described “games for girlthings with something wrong with them”.

An Australian protest group, Collective Shout, have claimed responsibility for pushing the payment processors and credit card firms into taking action against what they deem to be videogame glorifications of sexual violence and misogyny. As is now well-documented, Collective Shout’s good faith is heavily in doubt: founded by a “pro-life” feminist, they are affiliated with queerphobic religious rightwing groups who wish to criminalise sex work, and have form for mischaracterising things they want banned. They have also declined to share full details of the games they consider at fault, or how they identified and assessed them beyond searching for certain user tags.

Game devs and players affected by the policy changes have been pushing back. There’s now a counter-campaign underway to mass call Stripe, Paypal, Mastercard, Visa, Payoneer, PaySafe and Discover and harry them into changing course. The credit card and payment companies, meanwhile, are busily passing the buck, with Stripe attributing their leaning on Itch to pressure from one of their own financial partners, and Mastercard stonily insisting that they have “not evaluated any game or required restrictions of any activity on game creator sites and platforms”.

While following all this, I’ve had to confront my own ignorance about how exactly payment processors and related financial institutions work. Fortunately, being a journalist equipped with an email account, I have the means to start addressing that. Over the past week, I’ve been talking to a couple of academics about the role these companies have long played in upholding laws and policing notions of permissible sexual material.

Dr David L. Stearns is a former software engineer at Stripe, former senior lecturer at the University of Washington Information School, and the author of a book on the origins of the Visa electronic payment system. While not familiar with Itch, Steam and the adult content trade specifically, he gave me an opening steer on the ambiguous and changeable relationships between payment processors, the governments who produce laws and regulations, and the paying public.

A quick breakdown of the key financial parties involved in all this. On the one hand, there are the credit card companies and banks. Of those institutions, by far the most significant here are Visa and Mastercard, who account for the vast majority of all credit card transactions worldwide. On the other, there are payment processors, like Stripe – intermediaries who are licensed by the credit card companies and governments to handle the movement of money between a purchaser’s credit card company or bank and the bank of the merchant or seller.

The sheer ubiquity of Visa and Mastercard obliges them to play the part of extra-legal public guardians, enforcing laws by way of their control of economic activity. “In general, payment networks like Visa make revenue on every payment they process, so they have a natural incentive to process as many payments as possible,” Stearns told me over email. “But governments also have particular policies they want to enforce, and a convenient place for them to do that is via the banking and payments systems.

“To be a bank, or to move money, you need a license/charter from the government,” he continued. “In exchange for those licenses/charters, banks and payment networks become subject to government regulations. If the government decides to impose a regulation that restricts the processing of payments for particular kinds of goods within their jurisdiction, then the banks and networks must comply. If they don’t, they may face significant fines or have their licenses/charters revoked.” Smaller payment processors such as Stripe are similarly “deputized” into the process of ensuring that individual merchants comply with regulations, devising content policies of their own that reflect those of the credit card companies and banks they do business with.

Payment processors and credit card firms have long had a complicated relationship with the adult content business, because the transaction of sexually themed and explicit material tends to be defined as “high risk”.

“Remember that in most countries, cardholders can dispute transactions if they claim they didn’t actually authorize them, or if the goods were fraudulent, or defective, or never arrived,” Stearns told me. “When that occurs, the merchant becomes liable for the money and fees unless they can prove the transaction was legit. If the merchant goes bankrupt, the merchant processor or acquiring bank then becomes liable.”

If a merchant has a high rate of disputed transactions, and especially if the amounts in question are gigantic, payment processors or banks may take steps to protect themselves. They might ask the merchant to put money into an escrow – that is, a mutually agreed-upon third-party with the power to dole out cash to resolve disputes between merchants and customers. Or they might just stop handling transactions from the merchant altogether, to avoid eroding trust in the payment processing network as a whole.

“This dynamic often comes into play with highly-recognizable sites that specialize in adult content,” Stearns noted. “Stolen card credentials are often used to purchase subscriptions to such sites, and even legit transactions may get disputed when the partner of the cardholder sees it on the card statement.” He’s not, however, very versed on how adult content creators do business. For more on that front, I turned to the work of Dr Rébecca Franco, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Amsterdam’s Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences.

Franco is the author or co-author of several papers on the relationships between the adult content industry and the big finance firms. She has written extensively on the conflicts of interest inherent to asking big corporations to act as public safety sentinels, exploring how enforcement of regulations may slide into blanket, arse-covering suppression to avoid legal action or reputation damage when groups such as Collective Shout raise an outcry.

In a 2024 paper on “payment processing and the moral ordering of sexual content”, Franco looks at how payment processors may entangle compliance with brand management, and how this may lead to “definitional creep”, as payment processors or card companies begin to conflate illegal material such as recordings of child abuse with anything that might be deemed harmful by a sufficiently large or influential group of people.

This conflict of interest becomes even more acute when payment processors or credit card firms use or encourage the use of automated moderation tools, because AI moderation tools are ill-equipped to register context. They cannot reliably distinguish between, say, a BDSM fantasy with consenting performers and a recording of a rape. One, more light-hearted example of busted AI moderation is the possibility of videos being flagged as bestiality because a performer’s pet happened to wander through the background.

In another paper on the payment ecosystem and the regulation of adult webcamming and subscription-based fan platforms, Franco delves into the recent history of legislation and litigation against credit card companies that work with the adult content industry. She points to two pieces of linked legislation passed in the United States in 2018, the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act and Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act, which make credit card networks liable for potential involvement in criminal or civil litigation related to sex trafficking. She also cites a 2022 lawsuit against MindGeek, former owner of Pornhub, in which Visa was included as a defendant for allegedly profiting from Pornhub’s “trafficking venture”.

Responding to this changing legal environment, Mastercard introduced new global moderation and verification requirements in October 2021, with Visa rolling out similar policy changes in 2022. These changes have had a “devastating” effect on the livelihoods of adult content creators, Franco comments in her paper, and especially “queer, Black, kink, and fat sex workers” whose work may be considered self-evidently abhorrent by anti-porn organisations such as Exodus Cry – one of the co-signatories for Collective Shout’s recent campaign against Itch and Steam.

In her paper on webcamming, Franco suggests that Mastercard’s new requirements sometimes go beyond the letter of the law; they are as much defined by open-ended fears about profitability and market risk as they are precise legal definitions of obscenity and offensiveness. She posits that adult content is considered “high risk” by the payment networks because of wider social stigmatisation and the prospect of reputational damage – not because people who buy adult stuff are excessively prone to dispute transactions.

Could the game developer pushback against Mastercard, Visa and the payment processors succeed in overturning Steam and Itch.io’s policy changes regarding adult material? Again discussing the relationship between payment networks and merchants more generally, Stearns told me that it’s possible.

If governments are ultimately responsible for defining what’s acceptable, “these sorts of regulations are always a bit squishy and negotiable”, he explained. “Lawmakers do their best to encode desired policies into laws, and regulators do their best to encode those laws into industry regulations, but sometimes the end result is too broad and ill-defined.” If the regulations are felt to be unreasonable or unenforcable, merchants can and have forced a change by bandying together and making their case in the court of public opinion.

“If those merchants have significant leverage over the voting public (or the regulators/lawmakers directly through lobbying) they may choose to use that leverage to push back on the regulations,” Stearns went on. “If pressured enough, lawmakers and regulators often clarify the regulations or even amend the laws to placate those powerful merchants and their highly-motivated voting customers.”

Another, popular solution to the sex game crackdown on Itch and Steam is for the platform owners to find alternative payment providers such as Segpay, Vendo, and CCbill, who specialise in the transaction of adult material. Itch recently announced that they were looking into it. Speaking to me over email, Franco characterised this as a sensible approach, noting that “some high risk processors will help merchants completely manage the relationship with the bank, which is helpful for platforms who might have difficulties finding a suitable bank that is willing to have them as a client.” Adult payment processors may be able to bring clarity to people trying to work out whether their creations infringe upon the opaque and shifting provisions of the credit card companies and banks.

But there are caveats that might yet make pressuring the likes of Stripe and Mastercard to change tack the better strategy. Payment processors who cater to the adult content biz may have “significantly higher fees and strict compliance requirements”, Franco noted, especially in terms of KYC or Know Your Customer, aka the mandatory process of verifying a client’s identity. And then there is the question of which payment processor you can trust. “You’d have to find an established one, like CCbill,” Franco told me, “because unfortunately some adult payment processors can also make use of the high fees and margins without investing in compliance, and adult-specific payment processors have suddenly folded in the past.”