“Greebling” is George Lucas’s term for the decoration of spacecraft models with showy, superfluous details – clumps of antennae, bulky rivets, bulging pipes, anything that whiffs of function. Speaking as the human grown from the ashes of a child who once built the Death Star out of LEGO, I do enjoy a good greeble now and then, but it very easily becomes a parody of itself – like turning a machine inside out, but none of the exposed parts are meaningfully connected. Liliana, founder of Eridanus Industries and lead developer of space tactics sim Nebulous: Fleet Command, has more practical objections to greebling, based on her eight years in the US Navy: excess surface details are an absolute dust trap for radar waves.

“Every greeble on the surface of a ship is a radar cross-section magnifier,” Liliana tells me over videocall. “So you look at a real-life warship and they are flat surfaces. There’s no bevelling. The two edges come together at the perfect angle that they’re supposed to, and you limit the amount of stuff on the deck, because your RCS is a factor in how you live or die.” Hence the meticulously clean and faceted, utilitarian design of Fleet Command’s warships: if there’s anything mounted on the hull, it’s there for a purpose.

Watch on YouTube

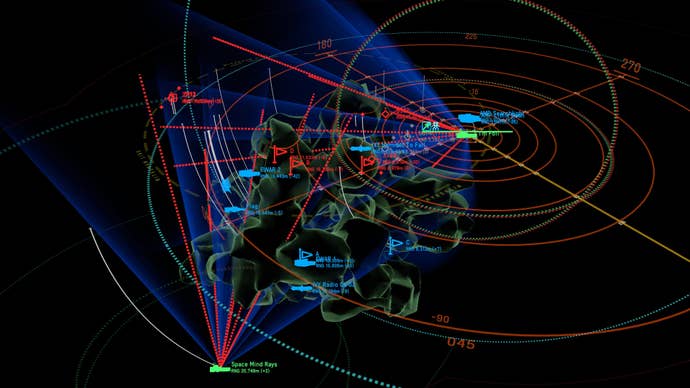

Radar operation is a complicated affair in Nebulous, extending far beyond the idea of “fog of war”. You think about it every time you set a heading. Turn a ship side-on to the other fleet (assuming you know its position) and you’re offering their radar waves a larger area to bounce off, while reflecting them directly back at the scanner. Fly ships close together and they’ll amplify each other’s radar signatures. Different types of internal radar module have different ranges, scanning aperture widths and power levels, to be weighed up gingerly against your points cap in the game’s fleet editor. And then you start to think about electronic warfare: jammers that spew a cone of interference, and conversely, burn-through sweeps that overclock a radar module to conquer that interference.

Nebulous doesn’t literally recreate the physics of all this, though I get the sense Liliana has given the idea serious consideration. It would be “prohibitive”, she says, to simulate actual radar waves in a “CPU-bound game” that is already trying to handle everything from the operation of individual, damageable components inside ships, to the antics of fighter craft and missiles. Rather, the game knows where every ship signature is at all times, then works out whether other craft can detect them through the cosmic white noise based on a bunch of competing factors.

“That includes things like checking if there is an asteroid in the way,” Liliana goes on. “Or measuring the distance and figuring out the attenuation of the signal there and back, multiplied by the cross section of the ship, depending on how it’s facing, and then the sensitivity of the radar, and then the noise floor of the map, which jammers raise.”

In short: “it simulates all of the physics of the wave travel, without having to process every single point in space that it could want to shoot away from”. The result is “as realistic as I think I can make it while still being performant.” It certainly feels very high fidelity in-game. I suck at radar tactics in Nebulous – I suck at most things in Nebulous, though I’m rapidly getting better at reading damage reports under pressure. But I’m in love with the idea that the slightest tweak to my ship’s heading could shrink my radar footprint a fraction and buy me an extra second or so to discreetly lock cannons on an approaching destroyer.

Liliana began making Nebulous partly just to hone what she’d learned during her earlier, academic career in hardware design, field robotics, and computer science. “Starting game development was kind of just a way for me to keep my skills sharp, because programming is a perishable skill,” she notes. But she also saw an opportunity to make a contribution to the real-time tactics genre, drawing on her military naval experience – in particular, the 3D space sim epitomised by Homeworld.

The latter’s influence on Nebulous can be traced from the abstract tactical view, which opens up a spherical hologram with distance measurements and icons, to the contours of the ships themselves, which evoke the designs of Rob Cunningham as much as Liliana’s understanding of radar reconnaissance. Still, her appreciation has limits. “I love Homeworld,” she says. “But one of the things that always got to me about it was that was how faceless everything was, and having served on a ship and seen how much goes into it, how much goes into everything, from keeping it running to getting it from point A to point B – there’s just so much that the games don’t capture, that I really wanted to capture.”

Take missiles. “When you take your missile ship in Homeworld and you right-click the enemy, they just dump all their missiles, and then they magically replenish them a little bit later,” Liliana goes on. “But in the real world, with the contents of our [vertical launching system] – when we would do briefings with the captains every day, we would put up a chart showing every missile in every VLS, and what their status was, which ones we could fire it and at what time, what was a casualty, that kind of stuff.

“Because every individual missile is so important, and the details of how to use them are so important. When I would train young ensigns, I would spend days and days and days going through the details of like, how the missiles launch, what their guidance systems look like, how we illuminate targets, that kind of stuff, because there’s just so much complexity, and I really wanted to capture that.”

You could spend days picking over the intricacies of missiles in Nebulous. Should they launch “hot”, immediately igniting their engines to reach the target as soon as possible, or “cold”, manoeuvring around the launching ship to acquire an unobstructed line of flight? Should they corkscrew or weave to avoid point defenses, and what should they do if they’re jammed and the target is lost?

The greatest feat of missile warfare in Nebulous is perhaps using “cruise” functionality to send missiles on circuitous routes toward enemy fleets. The multiplayer community’s best players will tee up several of these cruise patrols, timing them so that the missiles materialise all at once from different angles and overwhelm the target’s point defences. You can also build your own missiles in the editor, thickening their armour to withstand turret fire, and making trade-offs between range, main speed, acceleration and payload.

For all this finickiness, Liliana is not beholden to her real-life experience. She observes that “realism is a tool rather than a rule”, and is wary of sounding “elitist” with reference to wargame devs who aren’t from a military background. “You don’t need to have, like, a specific life experience to create a great game around something,” she comments. Still, firsthand knowledge of the practicalities is clearly what energises her work.

Another example is the user interface. While influenced by Homeworld, it shies away from contemporary software orthodoxy in consisting heavily of on-screen acronyms. “One of the things that really gets to me in a lot of UIs is picture buttons,” Liliana says. “For things like editors, they can work. Or like things where timeliness doesn’t matter. But everything that’s important in the Neb UI that you need to take action on, like the buttons at the bottom bar, for example, it’s all text, because I don’t want to [spend time] translating an image through my head into what it means. That’s not the way military interfaces work. They’re just words, words, words, words.”

While some parts of the interface feel directly inspired, others are more obviously fantastical. Take the damage control screen, which shows repair teams moving between ship compartments in real-time, dealing with problems in order of severity. Those repair staff can be killed by armour-piercing fire, so do try to rotate damaged components away from the fusillade.

“We didn’t have, like, a real time damage display [in the Navy],” Liliana says. “The way that we would do damage control is we basically have plates showing every level of the ship, and a full diagram of where everything is, and we draw on them with grease pencil as the team move around. And we get reports for like, this compartment has three inches of water on deck, this compartment has a fire in it, that kind of stuff. And so I translated that into a more visual, real-time kind of display in a way that was interesting.”

Liliana has found it intriguing and at times, alarming to see her ideas about naval warfare mutate even further in the hands of Fleet Command’s early access players. “There were assumptions that I made about how people would play the game based on my own expectations that just were not true of how the game’s mechanics incentivised play,” she says. One example is how players have favoured strength in numbers. “I view ships, for obvious reasons, as these extremely valuable assets. And so to me, obviously, anyone who played the game would fully build up their ship with damage control and as many weapons as possible, or what they could fit in the point costs.

“And then I gave it to a couple of experienced RTS players, and they just looked at the mechanics, and they went, well, it takes a lot more time to kill 10 empty ships than it does to kill two or three really well built-up ships. So I’m just going to do that. And so they basically made a bunch of expendable units, which is exactly what I didn’t want to happen. And so we tweaked mechanics to get around that. I learned a lot about incentivising the type of play that I want to see through mechanics.”

The game’s upcoming single player campaign will play a huge role here. Nebulous is currently a PvP-focussed experience with an AI skirmish mode. It offers an elegant and engaging set of tutorial missions, based on Liliana’s memories of training cadets, which are voiced by her wife. But as Liliana acknowledges, the current multiplayer scene is a rough ride for newcomers. “There are plenty of people who bounce off the game because they get into their first multiplayer battle and they just get annihilated by 100 missiles.”

The campaign will provide more of an on-ramp, though it sounds like PvP will remain the soul of Nebulous. “Now that all of the mechanics are in place, now that the carrier update is out, we can design a campaign which utilizes all of those things and provides like a nice, curated experience to get someone into the game experience.”

Another important consideration for solo players is, of course, fleshing out the AI. While working on the carriers update, Liliana made sweeping, secret adjustments to how non-player ships behave. The AI now groups ships into tactical archetypes based on factors such as hull type, armament and damage control configuration, then assigns a “captain” with a complementary behaviour. There’s also an “admiral” AI layer that picks a strategy based on the game mode, gives the captains orders, and switches things up depending on the fortunes of the match.

“There’s certainly some weird builds that it’s not optimized for, but [the AI] can, in general, look at the build of the ship, figure out the best way to use it, give it a captain that’s appropriate for how it’s supposed to fight,” Liliana says. “And then, at a strategic level, looking at the map, it can calculate based on how many points it controls, how long till the game ends, and whether it’s going to win or lose.” The new AI also has proper spatial awareness, which is enormously hard to accomplish in a 3D volume: it can use asteroids for cover without blocking its own shots.

Much as I disdain greebling above, I do worry that my enthusiasm for Nebulous is rather “greebly”. I’m fascinated by the complexity and gravitas Liliana’s knowledge brings to gambits I recognise from Homeworld. Coordinating a missile strike, step by step, is a wonderful piece of theatre. But the reframing of those moving parts as sci-fi fixtures also helps me forget that I am peering into the heart of a real-life war machine. The US Navy is not a box of LEGO, but an apparatus of power projection and control that spans the Earth and maintains a particular economic and social status quo. Given its frequent recourse to realism, I would like Fleet Command to explore that context, somehow.

I struggle to phrase this point during our interview, partly because my mind is awash with questions of radar etiquette, and partly because I’m trying to talk around the things Liliana isn’t able to discuss. “It’s not so much that I can’t talk about specific scenarios,” she comments. “Because pretty much when it comes to electronic warfare, the things that are actually classified are the specifics of, like frequency ranges for certain devices – what we can detect, what we can jam, that kind of stuff. But the actual principles of how it works, it’s all well-known and well-documented, and you can go online and just find all the equations, so that stuff is not sensitive. The thing I need to navigate carefully regarding my service is just like ethical concerns.” Amongst other things, Liliana is worried about the perception of cashing in; it is, she notes, “a violation of basically the integrity of your commission to use it for personal gain.”

I’m not expecting a storyline that offers a critique of the Navy, but I would like Nebulous to at least gesture toward the cultural histories and affordances of the technologies it asks you to fight with. What does it mean to interpret the world through radar? And conversely, what sort of community forms around the baroque, multiple-stage operation of such weapons?

Watch on YouTube

As her frequent anecdotes about shipboard life illustrate, Liliana seems keen to give some sense of warships as little floating societies, rather than just elaborate, “faceless” killing machines. Nebulous does simulate crew morale, with plans for warships to lose capability when their occupants panic. However adapted, its systems also retain something of their origins in the quotidian bustle of naval hierarchy and protocol. Radar operation is, as Liliana observes in passing, a work of many hands: it involves a division of roles, with some personnel searching for and others, tracking objects identified as potential threats.

Still, it’s hard to access that idea of a warship as a human collective through the format of a real-time tactics game that centralises the agency of one person – this being the kind of unity I imagine a living admiral would expect of their staff, for better and worse. I’m hopeful that, somewhere along the line, Nebulous will acquire a social texture on par with the abstract cleverness of its warfare. Part of what makes the tutorial effective is that feeling of having Liliana right at your elbow, showing you the ropes.