Morsels is a game best enjoyed by poison tasters. A roguelike pixelart shooter from Furcula and Annapurna Interactive, its world is a relentlessly aberrant waste dump in which it often feels like the only sure way to differentiate objects is to pop them in your mouth, and hope they don’t rupture, ignite or wriggle down your throat.

Video game science has yet to devise and normalise control devices that are operated with your tongue, despite notable efforts, so during my hands-on, I’m forced to fall back on my untrustworthy eyeballs. It’s an adventure. Developer Toby Dixon has to step in frequently to point out that some of the game’s oozing anomalies are there to empower me, not harm me. It helps that we meet at the end of Summer Game Fest and are both exhausted. It also helps that Dixon doesn’t seem entirely certain what some of the creatures are himself.

Watch on YouTube

“The little thing that you weren’t sure to do with, you can pick it up,” he says, after watching me oscillate gingerly away from what appears to be a hungry sinkclog. “Each time you pick up a Morsel, you get a little – we call it fuzzy, a little ball of squirming… something, and it’s actually a good thing. It’s a small stat upgrade. But people, almost universally, think it’s an enemy to stay away from. I’m not sure if I’m gonna fix that.”

I hope that Dixon doesn’t fix that. What I love about Morsels so far is that it is borderline unintelligible in places. While recognisably a top-down shmup in the Nuclear Throne tradition – and nowhere near as unearthly and elusive as, say, Relative Hell or a catamites project at its most fey – this is a game carried by fascination with certain shapes, colours and textures, almost to its undoing. It’s a nice holiday from the more professionalised and best-practicey games you tend to see at industry conventions that charge monstrous fees, in which the geometry of a creature or prop often teaches you instantly about its function.

“Obviously like, from a pure gameplay point of view, the ideal is just to have, like, you are a green circle, and all the bad things are red squares, on a black background,” Dixon comments. “And then everything’s perfectly readable and clear, and that’s like one side of things, and then, you try and make things pretty and give things interesting art. There is a bit of a compromise there, in terms of readability.”

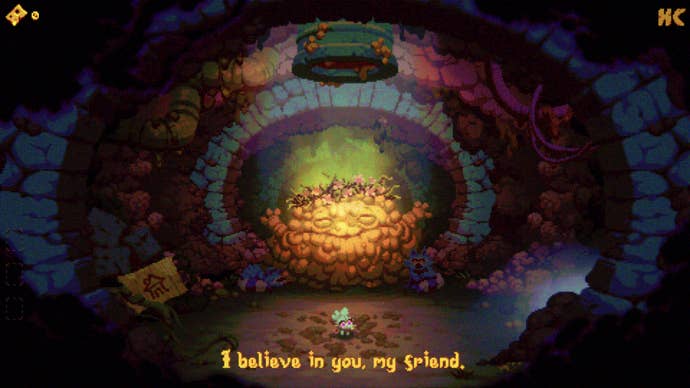

Morsels casts you as a wee mouse in a sewer, whose best friend is an enormous fatberg with the approximate demeanour of Zelda’s Great Deku Tree. Your goal is to travel upward and overthrow some villainous cats. The game’s 2D levels are linked by ladders in faint echo of Toejam and Earl, including bonus stages with bespoke rules. All are illustrated and animated with a greasy abandon that reminds me that the verb “render” can refer to the recycling of waste animal tissue.

One level is a maze of floating cosmic bullets. Another looks like moldy French cheese, where slain beasties puff into spores. A third is hung with rainclouds and snails. Each level is something of a noxious pinball machine, with powers, props and enemies that interact unpredictably. Dixon resists calling this an “ecosystem”, but notes that the dangers can often be pitted against each other. “That’s some of my favourite stuff in the game, to be honest. Because it always feels kind of better to kill an enemy indirectly, to be a little bit cunning.”

The joy of the game during your first stab at each level is naturally figuring these things out. What are the daisies for? Are there benefits to being turned into a frog? Where do the mouseholes lead? Is this conga eel to be trusted? Above all, what does this Morsel do? Morsels being the game’s collectible creature characters, which range from scrawny blue bottles to ambulatory sunflowers, each with a different attack and special ability. They can be tweaked a bit, with stats such as “Twitchy” and “Homely”, but this doesn’t seem to be one of those Destiny-grade hamster wheels that has you buildcrafting in your dreams. “It’s not one of those roguelikes with loads of unlocking stuff,” says Dixon. “It’s not really my cup of tea.”

What is Dixon’s cup of tea? I ask about his inspirations, and it gives him pause. “I struggle with these questions a little bit, because I often don’t really start with a clear idea consciously as I’m working. But I have mentioned I’m kind of quite into Jim Henson stuff. For this game, at least, I’m also trying to lean into kind of more my weirdest instincts, you know, just doing stuff because it’s kind of nice, or kind of gross and silly.” More obvious influences include cartoons of the 1990s: when Dixon brought Grindstone composer Sam Webster on to do the music, he told him to watch Hey Arnold.

Perhaps more than any specific taste or inclination, though, Dixon is driven by the idea that Morsels might be a one-off. “This is my first time sort of being in charge of a project like this,” he says. “And so basically I see it as an opportunity I might not get again. And so I feel like I want to go with my instincts. For me, I like stuff that’s a little bit ugly, a little bit mishappen, out of place. One of the influences for the game is probably, obviously Pokemon, and in some ways, I see it as being almost like a bizarro kind of version of Pokemon. I probably don’t want to name drop other games too much.”

He worries, nonetheless, that Morsels will simply throw a lot of players off, and in particular, that it will defeat the brains of journalists. When I comment apologetically that it’s rather awkward to ask artists to clinically categorise their influences, he replies: “Next time I make a game, first thing I’m going to do is, like, answer that question and like, I’ll base it on that.”

I am filled with sorrow that I have made Dixon doubt the dark and devious workings of his own imagination. Seeking to reassure him regret his game does have some kind of precedent, that it isn’t a UFO powered by brainfarts, I mention another, comparably grotesque and lurid game I’ve enjoyed recently about a pig princess who explores worlds in top-down, getting fatter as she eats things, to the point that she has to puke them back out in order to pass through the layout.

I can’t remember the name of the game, so I google “pig princess eating game” on my phone, and accidentally show Dixon some piggy princess pornography. Dixon takes this in his stride. “Um. Well, that’s cool, yeah. I mean, it sounds interesting.” Later, I check my Steam library and successfully identify the game I had in mind – Pig Eat Ball. It’s marvellous and disgusting, but not pornographic according to the usual metrics. Still, don’t let me tell you what to get off to.

I realise a lot of the above probably reads like the usual corpo journalist being lured marginally out of their comfort zone. This game does not look like an FPS minimap and is therefore Weird and Crazy. So let me finish with a slightly more specific, possibly worse framing: Morsels is kind of an effort to rescue the word “slop” from generative AI.

I didn’t discuss this with Dixon during the demo, and am at risk of putting words in his mouth, but the game’s premise of essentially shmuping upward through a vertical slice of landfill feels like an assertion of the artistic right to be incoherent, in the face of efforts to define incoherence as the algorithmic misreading of a disavowed dataset. Our brains are not machines for the production of orderly and correct art, but compost heaps whose emissions are unpredictable and unclean. It’s a pleasure to play a game that seems to play out the mucky and obscene excitement of making anything at all. You can get your teeth into the demo yourself on Steam.