In the realm of pixel artistry, action platformer Ninja Gaiden: Ragebound is a pretty work of dither and parallax. It’s full of set pieces reminiscent of a misremembered arcade’s heyday. Between the more standard run ‘n’ chop levels, there are jetski chasedowns, motorcycle pursuits, cargo train battles, bulldozer escapes, and gas chamber breakouts. If it didn’t frequently result in a death screen, I’d say it barely pauses for breath. The whole game is less a mineshaft of nostalgia as it is a shale fracking job, flushing you with jets of high pressure pseudomemory. I’m just a little sad that its strongest gimmick soon dissolves into the background, overwhelmed by floods of demon baddies.

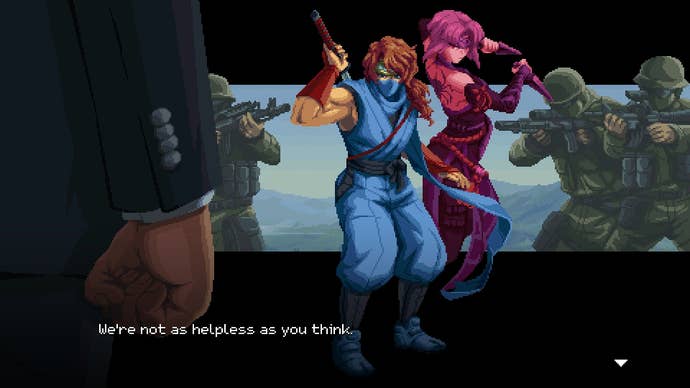

As you can probably tell, it’s a retro throwback to the Ninja Gaiden trilogy of yore, which originally appeared on NES and SNES in the 1990s. This is a sideways scrolling action wrecker full of dashing, slashing and ninja knife yeeting. The world is under threat by a demon lord who is manipulating those rascals in the CIA into releasing him from his infernal realm. You play a ninja lad (although not one fans will recognise) haunted by a purple-shaded phantom lass. Their clans are ancient enemies, but they’ve got to work together to get the demons stabbed. GO! ->

Watch on YouTube

Ninjaboy handles the close-range dicing, while Purplegal puffs in and out of existence to perform ranged kunai-throwing attacks over his shoulder. You can bounce off an enemy’s head (or their projectile attacks) with a second well-timed tap of the jump button as you collide, and a dodge-roll can get you past shielded foes for a quick back-shiv. Harness stabbyboy and floatygirl together by pressing both sword and ranged attack buttons simultaneously, and you’ll activate a superpowered blast of projectiles (you can also swap out this ultimate attack for other unlockable options later).

If this was all there was to Ragebound, I’d quickly throw it into RPS’ big pile of pixel-peppered nostalgia bait, along with all the other low-res revisitations that recreate the olden days without investigating the layers of game design that have accumulated like sediment in the intervening decades (hello, every PS1 tank controls horror game with fixed cameras and nothing interesting to say). Luckily, there’s one other fancy trick to Game Kitchen’s ninja antics.

Certain enemies glow blue or pink. Hit the blue buggers with the swordfella’s attack to become supercharged; cut down the pink pissants with ghostlady’s attack to become likewise charged-up. Mix up your colours by close-combatting a pink-coded baddie, for example, and you’ll miss out on the beefy glow of your next extra-powerful slice, an essential move you’ll need to cut down “blocker” enemies who slow down your sprint through the level. It’s only a thin layer of extra challenge, as you could technically batter your way through the whole game without using these super attacks. But the intention is clear: figure out a nippy run that instantaneously cuts down as many foes as possible in as quick a time as possible. This game is built for speedrunners.

In an earlier preview, I was impressed by the fluidity this feature granted to the levels. I liked that it leant into a “kill anything in one hit” philosophy – but only if you do things exactly in the right order, or with quick enough reflexes to at least fudge it. Those few enemies who took multiple whacks were sliceable in one bash, so long as you followed the patterns and pre-killed the correct enemy with the right-coloured attack.

But having now played the whole game, I’ve seen how this philosophy falters partway through. Many more enemies who require multiple slices appear, and sometimes even the glowing “charger” fodder who grant you that superslash will require more than one shanking. This does make it more challenging – something I’m sure plenty will relish – but it also slaps that sense of fluidity out of your hands and onto the floor. That’s especially true in later boss fights, where the rhythm becomes dictated by a classic pattern-discerning combat waltz.

You still need a fair amount of precision to get through levels, but I think that failure to commit hard to a totally precise lethality disappoints me. What early on seems like an invitation to dance and figure out a slick order of attack, becomes a more ordinary retro dash ‘n’ slash once you’re slowed by the weight of button bashing more and more often.

It’s not punitive in its restarts and checkpointing, at least. You’ll rarely lose more than a few seconds when you tumble into a pit. But some places could’ve been refined and shortened even more. Why send me five seconds back outside a boss gate if the only way for me to go is straight back in there? It would be better to instantaneously begin the boss fight again.

I especially grated at some of these bosses, which are beautifully rendered yet also the most typical genre element in the entire game, all pattern recognition and multi-phase wreckage. How I feel about the reflex-honing and the trial-by-game-over approach is dependent on mood, motivation, and whether or not I just like how things feel in my hands. Facing Genichiro in Sekiro after countless failed attempts resulted in a series of perfectly practiced steps which felt downright transcendent to perform perfectly. In Ragebound, defeating a weird mutant slimeball feels… I don’t know, rewarding, I guess? I get better at beating things, sure, but sometimes it’s only just enough to make up for the frustration of taking another electrical globule of spit to the face.

They’re hit and miss, rather than all terrible. I liked a big bad battleship that had me pinballing around its many eye-like turrets while soldiers took pot shots from me at the sides. I liked the twin mega eels who required me to use both blue and pink super-cuts in a strange act of one-person teamwork. I did not like the hulking apebeast who ejected spikey crystals at me. Mostly because these crystals were the “charger” enemies I needed to destroy to become hyperviolently charged, and you needed to hit these crystals three times to crack them and earn that juiceboost. There was barely enough time to hit these crystals once or twice before the beastbastard was standing right on top of me again. Go away, you zoo reject.

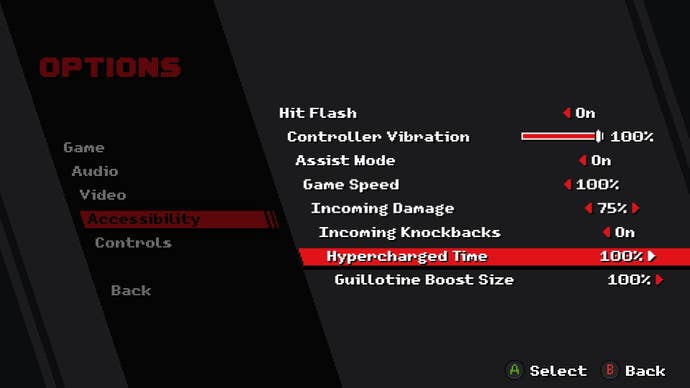

There is an assist mode, which might make some of my complaints moot, or might not. Generally speaking, I appreciate Kojima mentality of “pretend you won” when it comes to bosses. But Death Stranding 2 is a story-heavy game where bosses are wild outliers full of trash combat you haven’t been taught to expect. In something like Ninja Gaiden, the bosses arguably are the game. This makes me feel bad about bodging through them with a reduction to 75% damage or completely turning off knockbacks – assists I used more than once. It isn’t really meeting the game on its own terms. But I did make use of it, if only to speed the review along.

Before you get into a flame war over assist modes (they’re fine, shut up) you should know there’s also plenty here for masochists. For instance, you’ll sometimes find golden scarabs, which can be spent on special talismans between levels. This can mean bonuses, like a health cashback for kills, or tricksy new weapons for Ms Purple to cast through walls. But there are a bunch of others that handicap you for no other reason than providing an extra challenge. As I say, speedrunners: rejoice.

There is one talisman that sends you the whole way back to the beginning of the stage when you die (rather than simply the last checkpoint), and another that triples any damage you receive. This universal approach to difficulty – providing both assist modes and extra hard modes – is neat. I don’t think many people actually do complain in good faith about assist modes (sorry I told you to shut up) but to anyone who might, know that Ninja Gaiden: Ragebound runs a sharpening shuriken along the spectrum of difficulty, and it will cut you as deeply or as shallowly as you please. I put the damage down to 0% to get through a tough bit where you dangle from a helicopter. Meanwhile, you can remove all health pickups from every level. Knock yourself out.

I should also stress that none of this difficulty tweaking eventually fixed my disappointment about the loss of early levels’ sense of fluency. In games like this, where a steady flow is gained by practice, I sometimes wonder: what is the least amount of practice I must invest before I feel that sense of flow? In early sequences, Ragebound asks very little investment: you quickly earn a basic understanding of all the dashing, dodging, slashing, and boinging required to bloodstomp through an average level with a speedrunner’s abandon.

But later, particularly in some of those bosses, the time requirements for practice spike, and you’re forced to run the rigamarole of repetition expected of an arcade machine. This I have less desire to indulge, even if it does result in a game that feels like a perfect challenge for anyone who has finally drained all 50 games in UFO 50 of their sport. I can only speak for myself, someone who is effectively remembering a game I never actually played. Unsurprisingly, that anti-memory is not enough to goad me into the hard mode that appears, like a toothless boxer’s grin, when you complete the game.

Disclosure: Former RPS contributor Jay Castello did was a text editor on the game. I’ve also worked with narrative designer Jordi de Paco in the past.