For a low-stakes open world cycling game, Wheel World has a lot of lore. You wake up in the forest and discover a spirit called Skully, a ghost who offers the player a rusty bike and immediately ejects so much fantasy jargon and frontloaded backstory that I started to think it was an intentional joke. Thank Cog (the god of cycling) that this loredumping is not habitual. The rest of the game plays out as a chill and happy-hearted racer in a small but well-crafted world of rolling vineyards, bumpy forests, and honking city streets. It’s a short tour, lasting only about five hours, but it’s five hours nicely pedalled.

Your quest is to find the bicycle thieves who ran off with Skully’s magical bike parts – his wild wheels and arcane handlebars. There are deep cosmic consequences if you can’t get those back, we’re told, but mainly it’s an excuse to go exploring the small open world of twisting roads in search of racing events. There are a lot of colourful folk along the way, and any dialogue becomes much more relaxed and digestible than the initial blast of bike mythology. Bystanders chat idly about bike parts or local disturbances, all with copious bicycle slang. You’ll skid up next to gangs of cyclists and trash talk to kick off a race, battling wine connoisseurs through rows of grapes and corporate sales teams through industrial wastelands.

Watch on YouTube

The racing itself feels sleek and balanced, with a sense of coursing weight to the bike, especially on wide turns. Ride behind another cyclist to enter their slipstream and speed up, while also handily charging your magical boost bar. A lot of tracks include sneaky off-trail shortcuts, or ramps that you can bunny hop off with a flick of the joystick, and although there are no flashy tricks here, getting some air or narrowly avoiding cars and trucks will also charge up your boost. Crash and you’re plopped back on course with a refreshingly fast reset.

Getting into those slipstreams is useful for climbing positions, but it’s also important to know when you’re storming ahead – a rival can easily use the same tactic on you. I usually ended up strategically saving my boost for the final sprint. Which I believe is what real athlete-level cyclists do, when they are not busy taking steroids.

You’re rewarded with “rep”, a thumbs-uppy currency that you’ll need to accrue to face the boss-level rivals who have stolen your ghost buddy’s magic parts. A cocksure beer guzzler in one town might only require 12 rep before he’ll accept your challenge, but the moustachioed champ in the big city needs 40 rep, and a final boss will demand much more. In the meantime, you make do with parts won through standard races or found in glittering boxes sprinkled throughout the land, as if dumped in a ditch and marked delivered by Evri drivers.

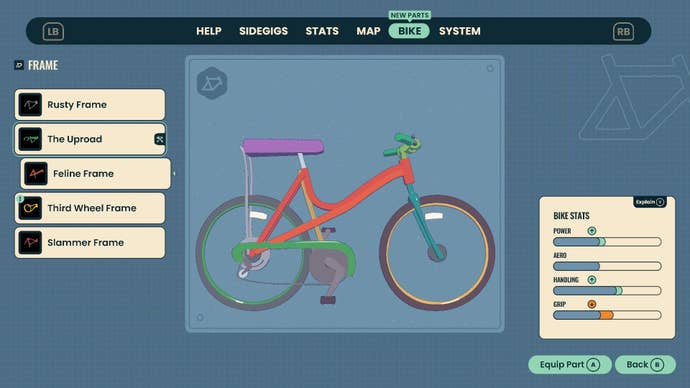

These parts alter your bike’s stats. Increasing “Power” gives you a better uphill pushing speed, for example, while “Aero” makes your ride more dynamic on the downhill. I found myself min-maxing in an effort to get an all-rounder bike, just because I can’t be arsed changing parts out for every race. That’s an option for anyone who cares enough about elevation maps, or wants to increase their “Handling” stat specifically for a race that’s all twisty turns. But I found it so quick to go from race to race that it was better to have one solid jack-of-all-gears. Racing games are about flow state, about staying in motion, and these kinds of arcadey open worlders in particular are often best enjoyed with as few trips into the menu as possible.

So aye. It ticks a lot of boxes for what I like in a racer. Its cartoony, cel-shaded presentation also brings to mind the bright skating of Olli Olli World. It’s silly and funny without trying too hard. Take Portal John, for example, a guy who’s invented a fast travel system using portapotties to harness the mystical and dangerous “sewer of spirits”. You’re not supposed to mess with that, he’s told. “Yeah, well I’m an entrepreneur,” he says, hammering a toilet. “I’m into disruption.”

It helps that all this colour is accompanied by an upbeat and hopeful soundtrack of mellow synth by Portland record label Italians Do It Better. It’s nigh impossible to feel stressed playing this game. Last week everyone in games media was celebrating the Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 3 + 4 remake as a great music discovery device. I see you and raise you Wheel World’s soundtrack.

However, with that supremely chill demanour comes a noticeable lack of real challenge. A well-balanced cycle and some cautious cornering will win you basically every race, difficult moments usually only presented by colliding into randomly passing traffic on an important bend, or getting donked by a rival as you pass. The game’s sometimes-shonky physics can also lead to a few upsets (or act in your favour, as rivals bounce into the sky or drive vertically up a wall like a zoomies-afflicted calico up the sitting room curtains).

Barring that, it’s not a tough thing to beat, and you’ll rack up the rep and coupons needed to reach the end faster than a yellow jacketed French roadster. This might put a few self-flagellists off but such brevity doesn’t bother me. There’s plenty of room in my life for a racing game you can coast through with all the friction of a summer breeze. I gnashed my teeth enough on JDM: Japanese Drift Master last month – a racing game that was good for its own tough reasons, but listen, I deserve an easy win.

The bike bonkers among you might more accurately compare it to the Descenders series, or Lonely Mountains: Downhill. Go ahead, I haven’t played enough of those to know. I find it more fun to think of Wheel World alongside 2023’s indie road trip game Season: A Letter To The Future, which had you bicycling around a small but detailed world in a similar vein. But while Season was an emotive story about memory and change given wheels and a camera, Wheel World is far more bubblegum and genre-loyal.

Some of the game’s design even veers close to Ubisoftian – you activate special shrines to reveal the map, little icons presenting themselves promptly for waypointing and cleaning up, after which you can peddle off towards one to begin a “side gig” for a corporate drone (discover five hidden jumps, etc). But then it redeems itself in other ways: you can, for instance, initiate some races by cycling up behind a rider and simply dinging your bell at them, which reminds me of the traffic light wheel-spinning of Burnout Paradise. If Burnout Paradise were a cel-shaded land of pushbikes and friendly ghosts instead of – ugh – DJ Atomika.

It’s a far cry from Messhof’s previous works – the incomparable Nidhogg remains one of the best fighting games of all time. And I’ll admit it feels a bit weird to set Wheel World’s sweet and ultimately harmless roamaround racing next to the snarling energy and electro fury of the fencing worm and its serpentine sequel. But that redefining of studio style feels inevitable when it expands beyond its origins – Messhof used to be a moniker for solo developer Mark Essen, but is now the name of his broader indie studio made up of many Messhoffers. If you’re going in expecting something similar to Nidhogg in tone, vibe, and surreality, you’ll only find trace amounts. But if you go in with a heart open to easygoing races and good music, Wheel World will quickly coast you through.